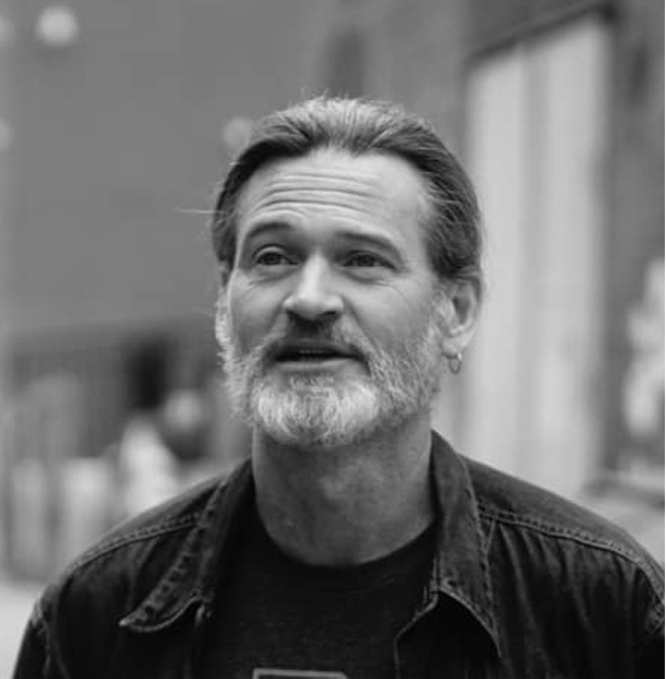

Amorak Huey is the author of four collections of poetry: Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy (Sundress Publications, 2021); Boom Box (Sundress Publications, 2019); Seducing the Asparagus Queen (Cloudbank Books, 2018), winner of the Vern Rutsala Poetry Prize; and Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress Publications, 2015).

He is also the author of two poetry chapbooks: The Insomniac Circus (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2014) and A Map of the Farm Three Miles from the End of Happy Hollow Road (Porkbelly Press, 2016).

He is the co-author, with W. Todd Kaneko, of Poetry: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology, published by Bloomsbury Academic in January 2018. The pair also wrote the poetry chapbook Slash/Slash, published in 2021. Slash/Slash was the winner of the Diode Editions Chapbook Prize. Huey is originally from Kalamazoo, Michigan, and grew up in Alabama. Previously, he taught at Grand Valley State University, and currently, Huey is a Professor of English at Bowling Green State University.

As of today, Auburn’s football team has yet to win a game against an SEC opponent and is 2nd to last in the SEC West. What is your opinion on the current state of the team and their future under coach Freeze?

You’re inviting me to write you an essay about how the hyper-Christian culture of college football is super toxic, especially in the South, especially in Alabama; how Hugh Freeze reminds me of the group of men who came to my house after I went to church at the First Baptist of Trussville with a junior-high friend, and their idea of outreach was to lecture my mother about how irresponsible it was that she didn’t seem to mind that her children were going to hell; how being a professor who cares about universities as sites of, you know, education means that being a serious fan of top-level Division I football is probably one of my most hypocritical traits; or maybe about how I suspect Freeze hired an offensive coordinator and gave him play-calling duties specifically so he could fire him at the end of this always-certain-to-be-a-struggle year and take over play-calling himself; or how nothing from Michael Lewis’ The Blind Side has aged all that well except for the part where Freeze comes across as stubborn and pious, self-righteous and self-interested — but anyway, Auburn has won a couple games in a row since you sent me this question, they should be bowl eligible in two weeks, and recruiting has turned around to keep their blue-chip index numbers acceptable after a few miserable seasons under a coach we don’t talk about anymore, so yeah, things are moving in the right direction.

Sorry for that, I couldn’t resist. On to poetry: Often times, your poems play a sort of balancing act with humor and devastating heartbreak. What role do you see humor inhabiting within your statements about some of the darkest truths of modern life?

Part of the job of poetry, I believe, is embodying contradiction. Poems reach for language that means more than one thing; words and phrases that evoke seemingly opposing concepts at once. So heartbreak and humor, yes. Not as opposite as we might think. Both essential in our humanity. This question makes me happy, because I want my poems to engage with humor, right, to be funny, or kind of funny, or almost funny, even as they’re also serious, but you never know how that’s going to land. Our senses of humor are so personal, so idiosyncratic; you put the poems out there and hope for the best. Of course, there’s also a long tradition of using humor as a way into the heavy stuff. Many of my favorite comics aren’t exactly telling jokes; they’re exploring really serious stories and subjects and getting laughs along the way. Tig Notaro, for example. One of the most amazing pieces of art I know is this live stand-up act she did right after finding out she had breast cancer, and she’s processing the diagnosis in almost real time with the audience, and she’s also funny, and it’s uncomfortable and terrible and great and amazing all at once. Not that my poems are anywhere near that level. But that’s what I’m chasing.

In Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy your poems mention the films E.T., Porky’s, Risky Business, Terminator, and reference others. What role has cinema played in the development of your voice as a poet?

Movies have been a huge part of my life. My parents divorced when I was kid, and my brother and I would spend weekends at our dad’s, and pretty much every weekend we went to the movies. Then I was like the exact right age for the video store explosion to be this, like, miracle — it’s hard to explain now, in terms that make sense in the streaming era, how crazy cool it was to be able to walk into a store in some strip mall and have this incredible array of movies available to you. Before we had kids, my wife and I went to the movies two or three times a week. As poets, as writers, as storytellers, we’re always casting about for models, for ways of perceiving, for the possibilities of narrative, and movies have always been a path toward possibility. Poets grab onto the language around them, the language they breathe in, and movies are tied up that language for me. Not just for me. For anyone growing up in the past fifty or sixty years. I mean, that’s also true of music, or TV, or any pop culture, really. Like, you read Shakespeare or Emily Dickinson or Natalie Diaz, you watch Top Gun, you listen to R.E.M. or Guns ‘N Roses or Public Enemy, you watch Game of Thrones or Andor, it all gets into your brain and rearranges you and shapes what you’re capable of making.

Can you talk a bit about the background and the inspiration behind the poem, “Self-Portrait as an Aging Clown Going for an Evening Run on the Summer Solstice?”

It will never stop being surreal to me that I grew up to be someone with a white-collar job living in a Midwestern suburb, a dad who likes puns and grills burgers and mows the lawn and coaches my kids’ second-grade soccer teams and periodically gets serious about running and losing weight. The very thought is absurd. Yet here I am, somehow.

Your work with titles always astounds me. My current favorite might be “The Existence of Han Solo Explains the Universe,” featured in your collection, Boom Box. When do you know a title is just right for an Amorak Huey poem?

Well, thanks. Man, I do love titles. Often in my writing process, the title comes before the poem. Ironically, this one didn’t, not in its final form. The poem was originally published in a now-defunct online journal under the title “Han Solo Explains the Universe,” but what I meant was that, like, the fact of Han Solo explained things, not that it’s a persona poem in Han’s voice or whatever, and so luckily I got another shot when the poem made the cut for the manuscript. How do I know when a title is just right? Definitely more an art than a science — sort of like how you can’t know as a 100 percent objective fact when a poem is finished, but the more poems you read and the more poems you write, you develop an instinct and a trust in that sense. I like titles that give the reader a starting place, a jumping-off point from which the poem can meander in all sorts of surprising directions. I like titles that are funnier than the poem. I like titles that make ridiculous promises. I like titles that offer a jolt of surprise from the very beginning of the reading process. I like titles that invite, that lure, that open a door. And I like the fact that there are lots of different kinds of work titles can do and that you can always find some new rhetorical strategy. Every poem offers a new opportunity.

How did your time as a reporter and an editor influence your evolution as a poet?

I wrote a lot of headlines in my time as an editor, which I think definitely plays into my appreciation for a good title. Maybe my best headline ever, one I actually won an award for, was on a story about a high school student who got suspended for wearing a Pepsi T-shirt to school on the day some Coca-Cola bigwig was coming to make a donation to the school. The headline was “Student calls Pepsi shirt a joke / but suspension the real thing.” Beyond headline writing, spending more than a decade in newspapers helped me hone my writing to the necessary — gave me practice saying complicated things in clear, concise language. I covered county government and a county-run hospital for a while in Elizabethtown, Ky., and so I’d have write these straightforward stories about sometimes-complicated meetings or legal topics. And of course these stories mattered, right? They mattered to the community, to the people affected by the county’s actions and decisions. Writing for a newspaper, you always had a very clear sense of audience and purpose. There was never anything abstract about the reason you were writing. I like to think I try to bring that same sense to my poems, even though poems do different work in the world than news articles — or maybe they do similar work in a different way.

I too am a huge fan of Jason Isbell’s music. I was pleasantly surprised when Isbell showed up alongside Leonard DiCaprio in Martin Scorsese’s new movie, Killers of the Flower Moon. Like Isbell, have you ever considered pursuing some cross-art-form work in acting, or any other field?

What’s the old saying about a face for radio, a voice for the newspaper? Teaching is as close as I’ll ever get to being on stage, I think. I can’t sing, I can’t even clap in rhythm, and I can barely draw a stick figure. Pretty sure words are where it’s at for me. Unless Scorsese has a bit part for me in a biopic about T.S. Eliot or something, which I’d happily take on. Call me, Marty!

What have you enjoyed most about starting River River Books?

Starting this press with Han VanderHart has been an incredibly rewarding experience. We’ve ushered two amazing books into the world already — An Eye in Each Square by Lauren Camp, Bullet Points by Jennifer A Sutherland — with the next two to follow in January. It’s been so much work, but good work, and a pleasure to do it alongside someone who values poetry and community as I do. We’ve learned a lot about the tedious parts and the costs — always, the costs! — of being a small press. We knew it would be hard, and in some ways it’s been harder than we expected, but it’s also an honor to support these books, these poets as best as we can.

What new projects do you have in the works?

My collaborator Todd Kaneko and I just finished going through the final proofs for the second edition of our textbook and anthology; that’ll be out in early 2024 from Bloomsbury. I have a manuscript I’m circulating. It’s called Mouth. I have a chapbook manuscript I’ve sent to a few places. I have this idea that my next book after Mouth might be new and collected prose poems, and with that in mind, I challenged my friend Chris Haven that both of us should write 15 new prose poems this month, so I’m working on that. I’m also very slowly writing a ttrpg set in a near-future, kind of cyberpunk, climate-change-ravaged, technology-dominated version of Michigan — which as I type that out, doesn’t sound as far from reality as I’d want it to. That one’s mostly just to give me a sandbox to play with worldbuilding for a while. I have no idea what, if anything, will become of the project. As you can see, I’m one of those people who tends to have too many projects in progress. I haven’t even told you about all of them.

For my last question, I’m going to steal a question from you. If you were going to read a poem, the same poem, every day for a year, which poem would it be?

For sure it’s “Song,” by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. The heart dies of this sweetness.

***

––Caleb Edmondson, Mid-American Review