On Thursday February 1st at 7:30pm, Poet and writer George Looney will be reading some of his work for the Spring 2024 Prout Chapel Reading Series at Bowling Green State University. The reading will be held in the Prout Chapel on the BGSU campus. The event is open to the public.

George Looney has nourished a decades long career as a successful writer, editor, and educator; his career has produced several collections of award-winning work: including, 13 collections of poetry and 4 collections of prose.

Looney’s work has been published in countless literary journals and anthologies such as American Writers Review and Mid-American Review in 2023 with his book review, Review of Wendell Mayo’s Twice-Born World: Stories of Lithuania and many, many more esteemed publications. His new short story collection The Visibility of Things Long Submerged was published by BOA Editions, LTD in 2023.

George Looney currently serves as a Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing and English at Penn State Erie where he also serves as the Editor of the literary journal, Lake Effect. Looney founded the BFA in Creative Writing Program at Penn State Erie. For eight years, Looney served as Editor-in-Chief of Mid-American Review after receiving his M.F.A. from Bowling Green State University; Looney now serves as the Translations Editor for Mid-American Review. We are incredibly lucky to have Looney back in Bowling Green this week; he will be reading from both his new book of stories, The Visibility of Things Long Submerged (BOA Editions) and his new collection of poetry, The Acrobatic Company of the Invisible (Cider Press Review).

To find out more information, visit George Looney here:

https://georgelooney.org/

Assistant Editor Elly Salah conducted the following interview with George Looney via email.

Elly Salah: You’ve mentioned that some of the places you write about in your fiction are real places. How do you decide what to fictionalize when drawing from real memories?

George Looney: None of the places in The Visibility of Things Long Submerged are actual places from my memory, places I have been and am remembering. But some of the places, like Rome, GA and Subligna, GA are real places that I had to use for various reasons. For instance, I needed a small town near the Chattahoochee National Park, as that National Park is a good place to find scarlet snakes, which was important for the story. I did quite a bit of research for both of these towns, because I wanted to have a sense of the places to fit the story to the place and to use the place to create the story. Research is always a two-lane highway in the creative process.

ES: In The Visibility of Things Long Submerged, your characters go through journeys where they question the role of faith in their lives. Would you mind sharing a little bit about how these character’s conflicts come to be: Does a character’s struggle come before the other elements of a narrative or does the narrative somehow shape the character’s struggle?

GL: In my estimation, plot is the least important element of fiction. Plot is just “this happens then this happens then this happens, etc.” The real question is, So what? And that comes from the interactions within and between characters. Putting characters in a setting and establishing conflict—or at least tension—is for me the genesis of story.

ES: How do you see poetry and prose influencing the ways in which we interact and create spaces of faith?

GL: Religion and faith are of course not the same thing. Art—all art, not just literature—no matter how nihilistic, has faith at its core. To make art is a positive act; it implies a faith in there being someone to “read” it, to experience it, to share the experience of it.

ES: Could you discuss a little bit about what it’s been like serving as an editor in the literary world and also a successful writer? Do those two “roles” ever conflict?

GL: I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to be an editor, first with Mid-American Review for many years and now with Lake Effect for many years. To get to participate in the shaping of contemporary poetry and prose—which is what literary journals do—is an honor. Editors say, this deserves to be read, this deserves an audience, this deserves to last. As for any conflict between being an editor and being a writer, the only conflict is the struggle for time. Reading the work of other writers—both good and bad—informs constantly my own skills as a writer. The two roles complement one another more than they conflict.

ES: What was it like to create the Bachelor’s of Fine Arts program at Penn State Erie? What motivated you to start the program?

GL: I was participating in one of those “retreats” to formulate a five-year plan for the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Penn State Erie, and I, sort of jokingly, suggested we should start a BFA in Creative Writing program. I had already revamped the BFA at BGSU before I left there to take a tenure-track position here (something I was never going to get at BGSU due to the attitudes of a particular Dean), and since we already had a well-funded reading series and a track in the English BA for creative writing, it seemed like a logical possibility. Then it turned out that the Chancellor loved the idea (thinking it would bring more females to a college dominated by males), and so I then had to spend a lot of time and energy creating the program, which I based on the work I had done at BGSU but trying to improve upon what I had done at BGSU.

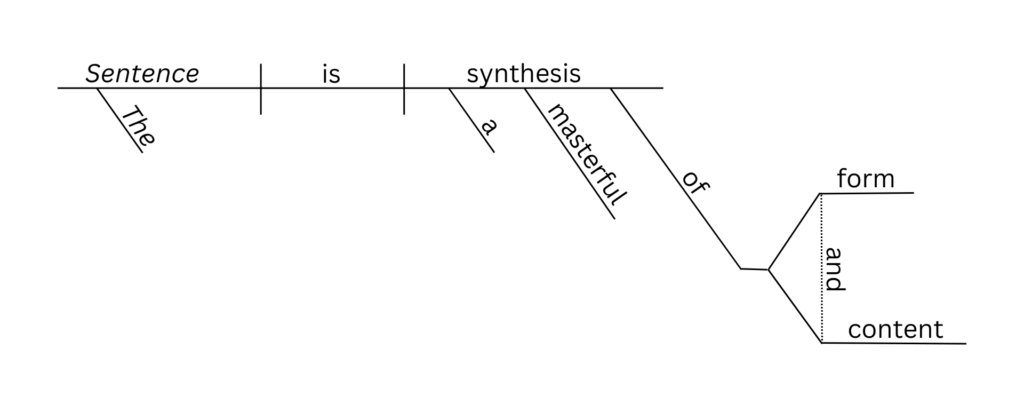

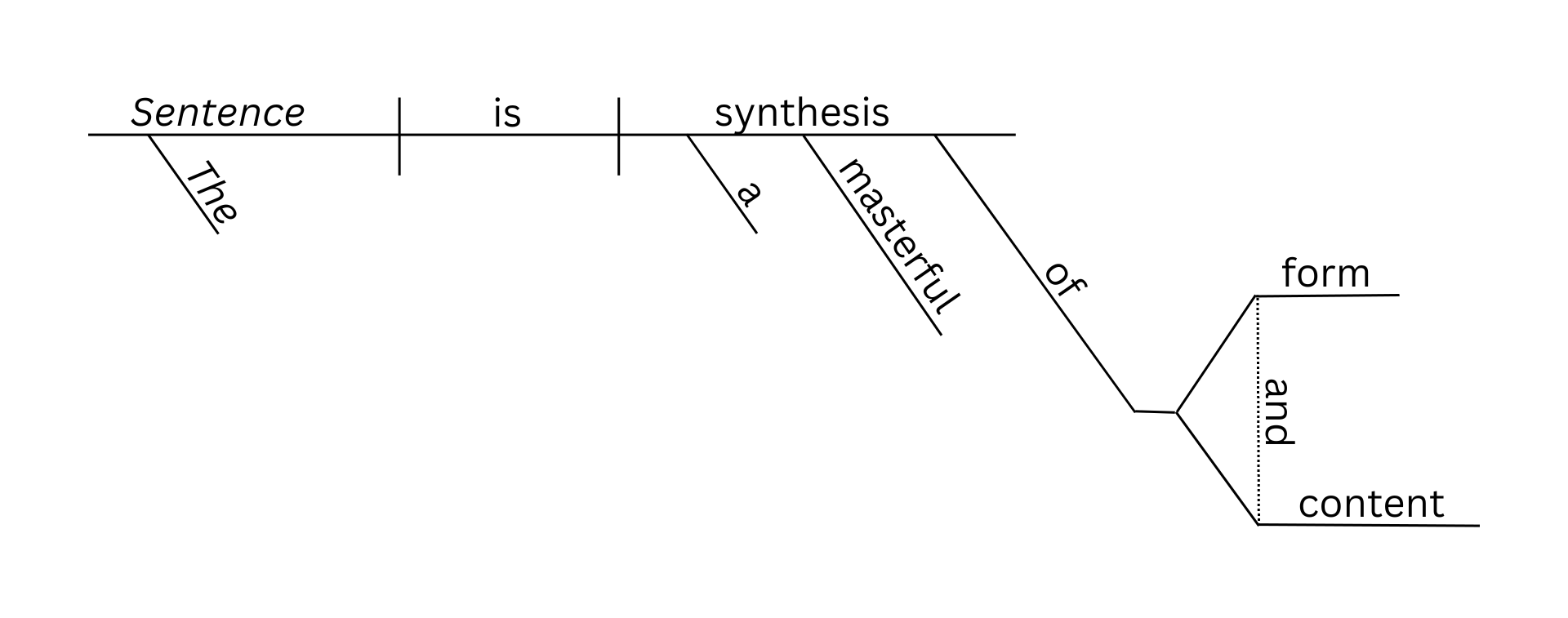

ES: Seeing as you are accomplished in multiple genres, would you mind sharing how your process might change when approaching a collection of prose versus a collection of poetry?

GL: The process doesn’t change, exactly. The focus is perhaps different. I agree with Ezra Pound, who argued that good poetry must be at least as well-written as good prose. The sentence is the basis of all good writing. Understanding how sentences function is essential in both poetry and prose. The only difference is in poetry you also have the line, which allows you to manipulate the sentence in an additional way. This does not include prose poetry, of course. But I realize you asked about producing collections of poetry or prose. Every book—whether prose or poetry—determines how it comes to be. The Visibility of Things Long Submerged started from one story—the first in the book—which was written as the result of a challenge like that which led to Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein. There were three of us—myself and two graduate fiction writers—sitting in a bar on Main Street drinking and waiting for a pool table to open up, and I said, in response to something, “Jesus is a shell game,” and one of the other two said someone should write a story with that title, so we all agreed to write such a story, and I was the only one who apparently was sober enough to remember. That was the original title of “What Gives Us Voice.” The editor of New England Review requested the title change. All the other stories came out of the feeling that the characters in that story had more to do, more to say, more to discover, more to reveal.

ES: As an expert in both poetry and prose, could you share with us a bit more about your process? This week you’ll be reading to us from both your collections of poetry and prose. Do you have any preference when it comes to reading your work?

GL: I have no preference between giving readings of my fiction or my poetry. But I should admit, even though I’ve published a novel, a novella, and two story collections, I consider myself a poet who has written some fiction. I love reading good fiction as much as I love reading good poetry, and I have fiction writers I feel as passionately about as I feel about my favorite poets.

ES: Reflecting on your time as an educator of creative writing, what is the single most important thing a creative writing student can take away from a course with you?

GL: A passionate love for language. And the recognition that—as Whitman declared about American poetry—the challenge is to create/discover language to express the inexpressible. To strive for anything less is to cheat yourself and, more importantly, to cheat the art of literature.

ES: Last question, what was your favorite place to hangout or thing to do when you attended Bowling Green State University for your MFA?

GL: There are several places and things I did, much with my best friend of 35 years who sadly died 5 years ago, Douglas Smith. Playing pool and ping pong at Howards, especially after workshop nights. Playing racketball at 2 or 3 in the morning after writing in Hanna Hall for hours in a court that used to be under the stadium and was always open, and then going to Frisch’s for breakfast, and then going home to sleep. There are others, but I’ll stop there.

***

––Elly Salah, Mid-American Review