Alyse Bensel serves as the Book Review Editor at The Los Angeles Review and Co-Editor at Beecher’s. She is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Not of Their Own Making (Dancing Girl Press, 2014) and Shift (Plan B Press, 2012). Her poems have most recently appeared in Heavy Feather Review, Sugar Mule, and Ruminate, among others. She is currently a PhD candidate in creative writing specializing in poetry at the University of Kansas. Her poem, “Glossary for Metamorphosis I,” appears in MAR 35.1. She’s here today on the blog to discuss poetry, cat-themed clothing, exposing family secrets, and more.

Quick! Summarize your poem in 10 words or fewer.

An exploration of 17th-century German vernacular for metamorphosis.

What can you share about this piece prior to its MAR publication?

“Glossary for Metamorphosis I” only took several revisions for me to be happy with it, but it was rejected 16 times before it found a home in MAR. I think the rejection count is on the low end for me.

I started working on the poem in January 2013. It was formed from a scattering of notes I had taken about Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), the subject of my manuscript-in-progress. All of the words explored in the poem are terms Merian initially used to describe metamorphosis. She didn’t know Latin, so she worked in the German vernacular for her observations. At that time my friend and I had a weekly Panera Bread workshop, where she suggested opening up the language more. I also got rid of a few sections, eulenfalter (nocturnal moths) and capellen (diurnal moths and butterflies), although they may reappear in other glossaries. This poem is only the first installment.

Coffee was most likely consumed during the writing and revision process.

What was your reaction upon receiving your MAR acceptance?

I danced around my house. My cats probably watched me. They do not approve of my dance habits.

What was the worst/best feedback you received on this piece (either in the writing/critiquing process, post-publication, or otherwise)?

I wrote this poem post-MFA, so the worst and best feedback was that I mostly had myself to converse with about the poem. This was a terrifying prospect.

You’re at a family reunion and some long-lost relative asks about your writing. What do you say?

“I wrote a poem revealing the family secrets.”

What do you consider your biggest writing-related success?

My first chapbook Shift, which Plan B Press accepted and published in 2012. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing with my writing, and that first chapbook acceptance opened doors for me. After that initial push for publication, everything became a lot easier. In the months that followed publication, I gave more readings, met more writers, poets, and publishers, and delved into becoming an editor myself.

Your biggest writing-related regret?

Going to graduate school nearly nonstop. The year I took off between my MFA and PhD was the time where I figured my writing out. I finally had time to breathe.

Tell us one strange thing about yourself that does not involve writing.

If there is a piece of clothing that features cats on it, I have to have it. There is no stopping me. I own a cat dress, a cat button-up shirt, a cat pullover sweatshirt, and multiple pairs of cat socks. I just need cat pants.

Do you have another favorite piece of writing in this MAR issue? If so, name it and tell us why.

How can I name only one? I think I’ve reread Luis García Montero’s work in the issue three or more times now. It’s so beautiful and haunting. He approaches the city and space from such a deeply engaged and fraught position I couldn’t help but take notice.

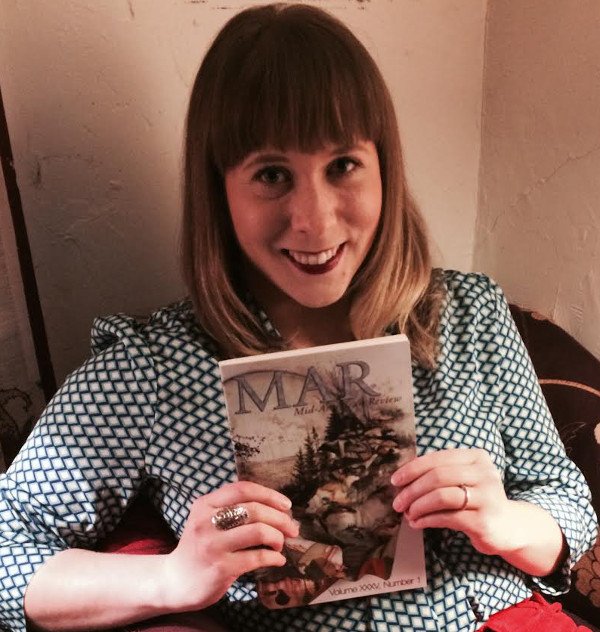

Can you show us a photo of you holding your MAR contributor’s copy?

Thanks for the interview, Alyse!

Thanks for the interview, Alyse!

Laura Maylene Walter, Fiction Editor