Katie Booth’s work has appeared in Indiana Review, Mid-American Review, The Fourth River and Vela, where she also edits the “Bookmarked” column. She has earned recognition and support for her work from the Edward Albee Foundation, the Blue Mountain Center and the Massachusetts Historical Society. She teaches writing and journalism at the University of Pittsburgh. Her creative nonfiction piece, “Still,” appears in MAR 35.1.

Quick! Summarize your piece in 10 words or fewer.

Excavator birds. Burned out house, brink of demolish. Flashback: fire.

What can you share about this piece prior to its MAR publication?

This was one of those pieces that I struggled with for years. I won’t bore you with the details of its many transformations and deletions. I will say that it only really broke into its current shape after I read “Stillness” by Charles Baxter, and let the piece unwrap around a single moment.

What was the best/worst feedback you received on this piece?

Once, after I read it aloud, a friend said, “It sounded like it was very beautiful, but I couldn’t actually hear you.”

What do you consider your biggest writing-related success?

I recently published a fiction story which was a thinly veiled story about my great-aunt’s experience as a native speaker of American Sign Language in an oralist deaf school in the 1930’s (where Sign was forbidden and punished). She had spent so much time, over years, letting me interview her, answering all these stupid questions I had—both for this story and a larger study of that moment in Deaf culture—but I’d never shared my writing with her. When I found out she had cancer, I was living in China. I couldn’t deliver it myself, but I finished the story and emailed it to my mother, who interpreted it into Sign Language for my aunt. It was published in Indiana Review this year, which was wonderful, but I was far happier to know that the story made it to my aunt, in her own language, before she died.

Do you have another favorite piece of writing in this MAR issue? If so, name it and tell us why.

Yes! At the risk of sounding like I didn’t read past the first piece, I’ll say that Jennifer K. Sweeny’s “Parenthetical at 35” is my favorite. She does this wonderful poetry-meets-essay thing that I’ve tried for years to pull off, but never really have—not like she does. The images she creates are so taut and layered; returning to it now, I’m shocked at how short the piece is. There’s such a full world within it, and such a quiet unfolding of the story that holds it together. I love this: “I had wished to live in a country of bad weather and nested inside a winter inside a winter inside a long night.” But for all the slow lingering of Sweeny’s piece, I also love the rushing thoughts of Wendy Cannella’s “Immortality,” and Nancy Hewitt’s “Measured,” both of which move breathlessly forward, ending in such unexpected ways, among the extension of the details we began with, but with expansive breadth.

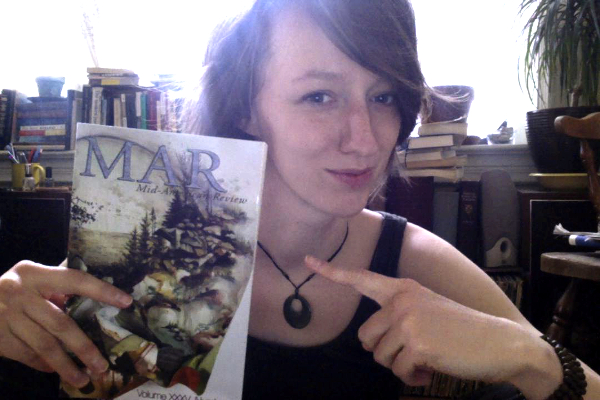

Can you show us a photo of you holding your MAR contributor’s copy?

Thanks for the interview, Katie!

Laura Maylene Walter, Fiction Editor