O-Jeremiah Agbaakin, a Nigerian poet, recently published his poem chapbook The Sign of the Ram in the New-Generation African Poets Chapbook Box Set series, Tisa, — an African Poet Fund (APFB) project set up for “poets who have not yet published their first full-length book of poetry.” Agbaakin, alongside ten other poets, features in the 2023 limited-edition box set. You can purchase The Sign of the Ram here.

In early days of writing poetry as a law student at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Agbaakin had not initially considered himself a ‘poet,’ even when he found his works in the pages of blooming literary platforms springing up here and there. Thinking about his journey of what he considers “self-confidence,” he’s thankful to have been nourished by the kind and warm support of friends and family. When he set out with publishing his poems first on social media like every other writer of his time, he had his “impressionable” non-writer friends and family believing he’s “the next Wole Soyinka and that the Nobel prize is finally coming home,” an endeavor that labors under the burden of great expectations.

When I first stumbled upon his poems published in the “World Rhyme and Rhythm–an anthology through their Briggite Poirson Poetry in 2016,” I was immediately smitten by his keen eye for detail and profound understanding of theology, human relationships, and behavior, and they weave together with such empathy and insight that make his poems feel destined, imbued with an almost prophetic quality. From “Isaac’s confession,” “Tenebrae,” “A thesis on language,” the speakers in Agbaakin’s poem are often on quests for self-discovery, not through outward ambition but through a deep desire to understand their social standing. They yearn to understand their place in the world, engaging in a constant dialogue with society and its reflections.

His poems are published in The Tems Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Cincinnati Review, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, EPOCH magazine, Guernica, Kenyon Review, POETRY Magazine, Harvard University’s TRANSITION magazine, Poetry Daily, Poetry Society of America, and “places where my favorite poets at the time have been published.” Agbaakin is currently pursuing a PhD in English with Creative Writing concentration at the University of Georgia.

I recently talked to Agbaakin over the email about his new chapbook, the story behind his poetry, and how he knew writing was the one after a string of trials with his lawyerly dream. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Photo credit: O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

This interview was conducted over email by MAR Assistant Editor Aishat Babatunde.

Interviewer

Congratulations on your first published collection! How do you find the experience?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

Thank you, Aishat. The experience has been cathartic for two reasons. One: it was a kind of release from some anger about a familial crisis which coincided with the period I was becoming more aware of my artistic vision. Two: it was a dream come true. I will focus on the second reason right away. I would say the feeling of both excitement and catharsis is no longer as familiar, like a vivid dream fades away upon full waking. When Siwar Masannat, the managing editor, reached out in January 2022 that Chris Abani and Kwame Dawes had selected the chapbook for publication, I couldn’t believe it. I’ve always wanted to be a part of the African Poetry Book Fund family. I had read many of the chapbooks from the series such as Warsan Shire’s Our Fathers do not belong to us, Gbenga Adesina’s Painter of Water, Ejiofor Ugwu’s The Book of God, Leila Chatti’s Ebb (among others); and even the full-length poetry collections like Clifton Gachagua’s Cartographer of Water. APBF has been and is doing a vital project of publishing, archiving, and promoting contemporary African poetry. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of that, right? Thanks to the generosity of previous authors under the series, I was nominated to submit a short manuscript sometime in 2018. I had no quality body of poems I was working on at the time. They rejected the manuscript. I think it was a karma for submitting such a mediocre work that they didn’t nominate me the following year! It was the year I wrote “Good Friday” , the poem which I think is very important (unknown to me at the time) to The Sign of the Ram. I emailed APBF to ask if they had nominated me but their email didn’t reach me (haha) but seriously my submission/contact email address had been deactivated by the University of Ibadan. They said they had not nominated me! The following year, they nominated me. I submitted; they rejected it! They asked me if I was interested in being nominated the following year. I said yes and submitted and they accepted it! I’m saying all these to express my gratitude to Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani for the trust and support they gave the tiny book. I don’t want to take my blessings for granted. They helped promote the chapbook boxset extensively with readings at the Africa Center in NYC and a virtual reading with Woodland Pattern book center. It is not often in the literary industry that publishers organize that level of publicity for a chapbook. Today, I don’t feel that way (elation) about the chapbook anymore. I feel like the speaker in The Sign of the Ram is now alien to me. It is a 2018 version of the speaker in my current poems; which means sometimes I am embarrassed by his audacity and vulnerability despite the mask of the persona of Isaac that I used! I am focusing whatever energies on my first full length poetry collection. One wonders what and how a future version of the speaker is going to look at the current speaker in my poems!

Interviewer

How has your experience in the US influenced your writing, if at all?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

This is an important question, one that I have mooted a response to so many times informally and formally. It’s also a tricky question because it assumes that the place (one moves to) automatically influences the art that’s produced; and therefore, if a Nigerian writer were to leave and start living outside of the country, their writing ceases to be Nigerian. While these assumptions are valid, it reduces influence to a cannibalistic process where the artist consumes everything in his immediate environment and the environment consumes the artist, spits out the artistic vomit to something alien or at worst, amorphous, all to the chagrin of the fundamentalist bemoaning the loss of an authentic native (substitute for Nigerian/African) writing. There has been much thought-provoking critical writing against the death of Nigerian literature. To their hubris, they believe their jeremiad is original; but its’ not. As long as people will not stop migrating (regardless of the motives), the discourse surrounding the authenticity of native art will not cease. All this to say this didn’t start today. Pius Adesanmi wrote about this issue in 2005, almost the same time the idea/movement of Afropolitanism was taking roots in African literature. It’s a deja vu for those that know history. Interestingly, this is what happens to the creatives who leave home. In a bid to stay ‘original’, the writer turns inward to nostalgia and memory. But that memory is fraught. It is unreliable in its recollection. The place called home doesn’t wait; it changes, such that memory as a literary expression is now foreign to the experience. Anyway, my short answer is that America has influenced my writing in the way that I hope I have described. Yet, it has allowed me to stop taking things for granted. Critics have not examined the problem of books and access to books back at home and how that limits the wide range of influence available to new creatives. Here, it is easier to obtain both historically important works and contemporary African books here than back home. Also, the themes that I didn’t pay attention to in Nigeria are starting to force their way into my creative interests.

Interviewer:

You have a background in law. When did you realize you fell in love with poetry more? Did your legal background influence your poetry in any way? Are there surprising connections between law and creative writing?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

How bold of you to imply that I fell out of love with law! Haha. The last time someone asked me last year– I think it was Maggie Graber during a poetry reading in Oxford, Mississippi– I told her that I didn’t have an answer for the question and if I found one I would reach out to her. I said that because it was a live interview and I couldn’t think on my feet for an appropriate and honest response. With you, I have an advantage of mulling over the question longer (Gotcha!). But really, this goes back to the previous question on influence. No experience is immaterial to any artist. One of the ways by which I determine the maturity of a poem I am working is by asking myself: has it, i.e. the speaker and the poem undergone an experience (vicariously through me of course) commensurate with the ambition of abstract language? Does it possess any wisdom that one often gains through a process by which the experience is aware of (and even documents) its own prior inexperiece? You need to go through the fire to be able to have a language for some kinds of writings. I am in that stage where the experience of being trained as a lawyer (without one year of Nigerian law school and call-to-bar experience that I am sure you know about!) has yet to present itself as a conscious material in my work, as a project; or even where it may exert some influence, I am unaware of it; which means that it doesn’t matter what I say now. The influence may just be outside the threshold of perception, but it is potentially there or not. I don’t think my writing would have been different if I had studied English or architecture or anatomy! But maybe in the future, I would produce a work that explores that intersection between law and art or raid all the knowledge I have gained from studying law for five years, the way M. NourbeSe Philip, the Canadian writer and poet used her training as a lawyer to write the haunting book, Zong! about the Zong massacre. I knew I always wanted to do creative writing even before I started studying law at the University of Ibadan. If you remember correctly in our last interview with Tell! Magazine I have always inhabited the world of story-creation (and later on, poetry) since I was very young. Do you remember our interview on Tell? And to what degree do you think you have grown as a journalist and brilliant book and culture commentator?

Interviewer:

Absolutely! It’s fantastic to hear from someone who remembers our chat on Tell. I may not recall the specifics after so many interviews, I do appreciate our interview on Tell! magazine.

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

As for how I’ve grown, well, I think anyone with a curious mind keeps evolving, you know? I think the more I delve into different stories and the more I’m let in on people’s personal experiences, the richer my understanding of the world has become. Maybe my writing has matured a bit, hopefully in a way that keeps things interesting!

Interviewer:

Earlier, you argued against the idea that a writer who leaves Nigeria loses the ability to write authentically Nigerian literature. What are your thoughts on the counterargument that perhaps a writer’s physical distance from their home country can lead to a more critical or objective perspective on their society, in a different way that enriches their work?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

I think I started taking my writing more seriously after that interview! It’s like “look I made it” moment for me at the time (haha). Growth is scary. It is unpredictable. You think you know it all now; wait for a couple of years! That is my guiding principle whenever I try to express an opinion on something. But the fear of growth shouldn’t stop one from sharing an opinion or thoughts. It is better that one has the opportunity to be wrong now and grow through it than one to have no opinion at all. This is a good counterargument. My opinion on the idea of alienation of the Nigerian writer both physically and psychologically is that it is inevitable, as inevitable as migration. The writer must do with it whatever they see fit with their condition. One’s work will not automatically enjoy the benefits of distance (such as clarity, foresight, objective perspective, and so on) by that virtue of removing oneself alone. It’s like going to the mountain, doing nothing, and expecting the rewards. The ascent is only an element of the process. You must scream at/on the mountain to test the timbre of your own echo and carve a voice out of it; you must sit and pray before transfiguration can happen. You must be disciplined to not be carried away by the relative ease you have now found and forget the condition of your life, which although is now past and lost (lost because it’s severed from place, time and one’s psyche). You must also climb down from the mountain. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the descent is harder than the ascent. You need patience unless one may be stuck on a plateau to find that the landscape has changed. It reminds me of the speaker in Safia Elhillo’s ”origin story” from her January Children collection whose grandmother upon her physical return to the homeland tells her to “shred dill / by hand she means to teach me patience she calls it length of mind”. Afterwards the grandfather reminds her ”it is time to come home”. I guess I’m speaking too much in metaphors but that’s the best way I can respond. Staying away from home can create a disconnect between the writer and the temporal realities of home, yet it gives the alienated writer the opportunity to be free from the clock(work) of the society’s psyche. I think it was Charles Simic that quipped that it is the ambition of lyric poetry to stop time. If that is true, then the alienated poet can hold on longer to that momentary pause.

Interviewer:

In your poem “towing // or the book of isaac I” (published in The Temz Review), there are elements that seem both personal and observational. Can you talk about how you navigate the tension between memory and observation in your writing, particularly when it comes to capturing the speaker’s blackness?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

This one is tough because that’s a really old poem (written in 2018 and published 2019 I believe) And your question suggests that I still navigate the tension between memory and observation the way I navigated it “Towing…”. Talking about growth, that will not be the case! At the time that I wrote the poem– and this is true for all the poems I was writing at the time– I wasn’t aware that there’s tension between memory and observation in writing that poem. But the very nature and the relationship between memory and observation is fraught with tension. One deals with sensory data captured instantaneously while the other is a matter of data retrieval and the subsequent iteration and reiteration of data. One lives in the moment, the other lives in the past and desperately wants to live in the moment. But the moment even the present is reproduced in words or strokes of color, it ceases to merely be a matter of observation. Now that I am more grown, I try to play the role of a mediator between the two. I honor memory; I remind the present it, too is a vapor. So there really is no tension. Because the moment will also become a vapor, I must live in it. I must write about my immediate environment . I have written about Oxford, Mississippi. During a hang out with one of my professors, Beth Ann Fenelly and other new students in January 2021, I shared the fact that James Meredith, the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi, travelled to Nigeria to continue his education in Political Science at our alma mater, University of Ibadan. Seeing the reverse-parallel between us, she challenged me to write about that. I didn’t! (In my defence, she didn’t state in what genre I should write it!) Instead I wrote about the 14-year old black boy, George Stinney jr., the youngest person to be executed by the electric chair in the United States, in my poem, “Devotion” , one of the poems in The Sign of the Ram. What tension can possibly exist in writing a poem like “Towing”? I was not Black at the time in Nigeria the way I would now be considered black in America. The speaker in the poem is Isaac, who is an object of near-sacrifice the way black bodies are in the history of civilization. By using the persona of Isaac, it becomes easy to collapse collective memory of a cult figure in Abrahamic tradition and a racialized body/site of violence with an active observation of an event of being on the road at the time I wrote the poem.

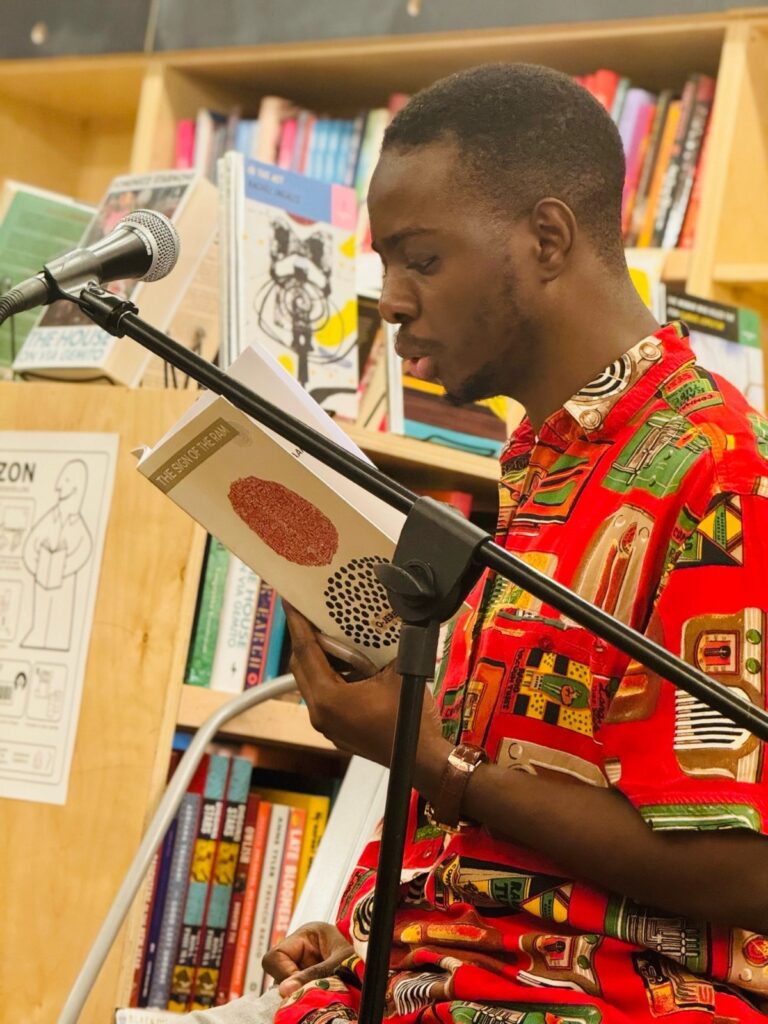

Photo caption: Agbaakin reads from his newly published chapbook to an audience at the University of Georgia.

Interviewer:

Do you see a role for African writers in the diaspora to bridge this gap in access to books back home? Perhaps through advocating for increased literary resources or even incorporating those limitations into their work?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

I think it will be unfair to task the nomadists with solving all the problems with our literature. The problem of the dearth of literary resources is on an institutional scale, and requires an institutional solution. I think this is one of the innovations of the African Poetry Book Fund Libraries. Currently, they have libraries in six African countries. That is a huge stride! Despite the pessimism of many critics about the death of Nigerian literature, there has been a renaissance in the system of support. I think Kanyinsola Olorunnisola (whom we both know) wrote about this in his essay, “Our Literature has died again” where he declared himself among other japa writers the nomadist movement. This is a more interesting term than Afropolitanism. Anyway, he lists the plethora of prizes, journals, editorial fellowships, grants, seminars and so on that are actively promoting Nigerian and African literature at large. Like I have mentioned, the government has to involve someone. The scale of the solution must match the scale of the problem. I have chosen to be optimistic. We, writers in the diaspora and at home can be the impulse that sets the wheel in motion. If not us, who will?

Interviewer:

Given your experience living in liminal spaces, how do you define your relationship to Nigeria?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

It depends on the time of the day, seriously! (Haha). It’s a frustrating relationship, really. I hate that the country has created and sustained the conditions that would make a majority of its youth want to leave in droves every year. Now my generation may want to think that they are in exile, but that is not entirely true. I think it was in Teju Cole’s Open City where Julius in his interaction with Farouq said something along the line that we are not in exile if we can always return. To quote directly, Farouq says: “To be a writer in exile is a great thing. But what is exile now, when everyone goes and comes freely?” If I am in no exile, then what/where am I? The question is important because what I am defines my relationship with my native land. Clearly, I still don’t have the mobility capital of the Afropolitan; which is why I don’t identify as an Afropolitan, to answer your previous question. Yet, I (this is true for many of us) have a unique set of circumstances that is close to being in a state of exile. If I have to travel outside of the United States (to Nigeria of course), I have to renew my expired VISA; to go through the humiliating immigration process again. You are reminded that you’re an ‘alien’ anytime you apply for an opportunity that requires an American residency. I have defined my relationship to Nigeria as that of being a Nigerian. For all the respect that Nigerians command worldwide, the country itself commands none. Therefore, I am proudly Nigerian but feel nothing for the country itself beyond the feeling of frustration. I am not sure if I have experience living in liminal spaces. Some days, you feel fully Nigerian, Your voice comes to you unchanged. Other days, there is a great sense of spatial disorientation that you even feel it physically in your body. I guess it’s the same experience as speaking English. English is our language. Where we are right now (the place, the culture, the history) is a kind of home. If not? Then what is it?

Interviewer:

What is your writing process like? Do you have a specific routine or preferred environment for writing poems?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

I am a very slow writer. I envy many of my friends who are able to write a poem at a go. I write lines that add up over time and when I have a coherent draft, I take forever to revise it. Writing is like planting for me. My best planting season is sentimentally in April where I have a better structure. I write a poem a day for the whole month, then trash like a half or three quarter of the poems and revise the rest for the rest of the year. Outside of this ritual, I don’t write a routine. I prefer writing while on the bus or while I am walking. In the past, this is what I did during the revision stage: I take the poem on a walk until it’s forced to say something of its own accord, not what I have written into its medium. Now, I walk to get the writing out.

Photo Caption: A copy of The Sign of the Ram.

Interviewer:

Can you share a poem from your collection that resonates with you personally, and tell us a bit about its inspiration?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

All the poems in the chapbook resonate with me personally because I poured my heart into them. It is a collection about being vulnerable and confronting the alienation between a father and a son, told through the lens of the sacrifice of Isaac. The story has been told many times in Christianity and Islam as a testament to the faith(fulness) of Abraham. It is a story of man-divine relationship, while largely devaluing the man-man dimension of the story. Talking of liminal spaces, it is a story of the liminal space of awkward silence between a father and a son on their way back from the foiled sacrifice. If the two patriarchs were to talk as one mortal to another, what would their conversation be about? There is the subject of forgiveness, which inscribes itself as a divine virtue. Another question is that what about the conversation between Isaac and God during the whole episode, without the appositive insertion of Abraham? Was Abraham God in that moment he took full control of his life and the language used to mediate or excuse the exercise of tyrannical power? In what ways do men in patriarchal societies embody the voice of God to abuse their own power and cause violence? I think that is the broader question I was asking in The Sign of the Ram.

Anyway, if this chapbook had only one poem in it, that poem would be “Good Friday”. I feel that is my most authentic poem ever. I have not been able to reproduce the moves I made into my other poems, especially the compact structure, the wirework of allusion, personal history and communal memory embedded, and so on. It starts with a dialogue with a divine son and a divine father who sucks at snake charming; father as in God. The snake as in the serpent. It takes the risk of being iconoclastic but (let me tell you) it becomes less irreverent when I tell you that the father is also a physical father and the speaker is a physical son. One day, a spitting cobra (Sebe) entered our living room while my brother and I were watching a movie at midnight. The electricity had been coming in a low current for a few days. One midnight, the bulbs shone brighter (because people were sleeping and not using their home gadgets) so my brother and I decided to watch a movie that we’ve been burning to watch. I think the title is Sekeseke (boundage), Yomi Ogunmola was the main character. You can guess where this anecdote is going: if we weren’t watching the movie that night, there’s no telling what the snake would have done undetected. Anyway, the snake slithered away when it saw that it was exposed. My father said we should leave the snake. That it was not coming back! The other men in the house (it was a family house) insisted that we hunted the snake down. Lo and behold, the snake was slithering back into the house again. I don’t remember much else from that night but my father’s psyche was interesting. If we had listened to him… yet, maybe he could have been too tired after a hard day’s job, or maybe he’s just pro-animal rights (haha). We never had this conversation till date so we are still living in a liminal space about that incident.

Interviewer:

What are some of your favorite things about being a poet? What are some of the challenges?

O-Jeremiah Agbaakin:

Easy one. I use a mask, to cast the shadow of a truth! The truth is difficult, too bright and stark to look at so sometimes it is better to look at it at an angle (Dickison’s tell the truth slightly?) or wear goggles, or like me, wear a mask! By mask, I mean the persona of other mythological (and often Biblical stories). That is my signature move that finds antecedence in my beloved Peter Weltner, among many other poets. The mask allows me to blend private ethos with a more universal mythos. Which is why I love it when other poets go into their poems with a raw face. How do you do that? I don’t consider myself too interesting to expose myself in my poetry. Yet, there are moments I feel naked when I read my poems and I get it. The feeling comes with a sense of satisfaction that I am the only one privy to a fact in the poem, and that comes with its own catharsis as well. The most important thing is that my language must take control of the poem. This reminds me of what Jessie Nathan said of Richie Hoffman’s: ““All technique, no passion, a critic said” of Canadian pianist Louis Lortie, “but,” writes Richie Hofmann, “that was what I liked.” It’s as if what moves the poet is not the feeling directly, but the way that feeling emanates from the completeness of its subordination to the craft.” At the end of the day, we are not special. At the end of the day, our suffering is not special but it is ours. The greatest pleasure I get as a poet is when a revision goes well. It is when the poem finally speaks! Another favorite thing is when I am able to finally document a childhood experience, a haunting into an artistic language that doesn’t call attention to the experience itself but ruptures the temporal prison where they used to be. It was not that I forgot those things, but that before I knew I was a poet, I didn’t know what to do with them. Thank God I am a poet. The greatest challenge of being a poet is how do you live outside of the impulse to literalize every single experience that’s happening now? How do you live in the moment without trying to make meaning out of it? It is almost like going to a vacation in paradise with a camera. If you don’t capture it, you can’t remember and write it as it was; but if you write it, you are not enjoying the beauty viscerally. It’s hard! But sometimes, I deliberately forget that I am a poet. That helps.

Interviewer:

Thank you so much for your time.