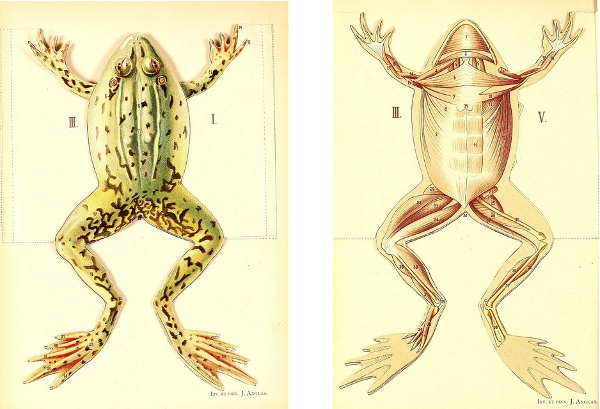

Here is the second installment of Suzanne Hodsden’s three-part series, “How I Almost Met Dan Stevens Eight Times on a Mission from MAR.” Read the first part, “The MFA Can Kill You,” and stayed tuned for Part III, which will go live early next week. (Frog dissection images: Biodiversity Heritage Library)

Part II – Gaddafi, Frogs, and Jungian Beetles

By Suzanne Hodsden

My father started tailing me to my doctor’s appointments. He just strolled in and sat down as if he also had an appointment. The first time, he ignored me entirely and picked up a three-year-old issue of Time. When I asked what he was doing there, he lowered the magazine just far enough so he could see me, and said “Your mother made me” with a meaningful stare. One day you’ll have been married for 39 years, it said—and you’ll look back on this moment and forgive me. He disappeared again behind the face of Muammar Gaddafi.

Later when I told my mother to call off my bodyguard, she insisted that she hadn’t made him do anything. “I simply said that if he was interested in being a good father, he should want to go with you.” There is a distinction there that only my mother can see.

“You found a job yet?” Gaddafi asked me.

The MFA degree qualifies a girl for everything and nothing at the same time. Applying anywhere outside academia requires a bit of spin, but—luckily—bullshit is one of our specialties. I cast my job net wide. I applied to everything and interviewed everywhere.

There was one listing for a receptionist position that specified the office’s 76 houseplants. How big was this office? What kind of plants? A venus fly-trap that ate people who failed to rinse their coffee cup? Was this why there was an opening? With motivations less than pure, I applied.

On the day before my first surgery, I interviewed for a retail job in an upscale sex-store. I spun a story about the need for a freer world for female sexual expression so fraught with emotion I thought the manager was going to cry. She offered me the job on the spot, but at part time and minimum wage, I declined.

I changed my clothes and collapsed face first into the dirt of Lincoln Park. I laid there and wondered if I’d been too hasty in turning down a paying job. Then I thought about the long forgotten formaldehyde-d frog I’d dissected in 7th grade. My disrespectful “Ewwww” as I tore open its poor body and laid its innards open to the wind. That poor frog had returned to seek vengeance, I was sure of it. I stayed there in the dirt until my presence started to scare the children. I thought about having my drink.

During my pre-surgery interview, I’d worked in a question of my own. How bad was it—on a scale from one to a winter invasion of Russia—to consider having a drink? The surgeon approved me for one. Just one, and no more.

Picking myself up out of the dirt, I decided it was time. I didn’t want company for this drink. Not at all. I couldn’t endure any wet-eyelashed speeches about how I was going to be “fine.” I chose a bar on W. 14th, on my way home. It was an out of the way spot and nearly empty. Perfect. I sat down outside and tried to forget about the frog. Then I thought about the frog and drew pictures of the frog.

Seconds after I ordered a Limoncello martini, I heard a British accent behind me. Surely not. No. There’s more than one British person in Cleveland. No. no. no. no. no. I turned. Yes.

Less than two feet from my elbow, there he was. Dan Stevens. He’d had a haircut (A perm, the poor bastard.), but it was him. I looked down at myself. I was grass and sweat stained. I was on the verge of throwing up. The corner of MAR issue 34.1 poked out of my purse and mocked me.

The uncharacteristic ebullience of the entire female wait staff should have tipped me off. If his effect on an ordinarily jaded Cleveland waitress can be used to measure stardom, this guy is going to be a movie star for a very long time.

“You saw him again? By sheer freaking accident?” Despite her earlier confidence, Abby was surprised too. “What did you do?”

“Nothing.”

“Why not?”

I wanted to say something, I did. I really did, but the only thing I could think of to say was this: “What are you? The goddamn angel of death?”

***

When I was wheeling my way towards surgery the next morning, the surgeon remarked on my mood, but I didn’t explain it. I knew it was absurd, but I was pretty convinced. I’d seen Dan Stevens twice. I was going to die.

Luckily I had the presence of mind to keep it to myself. Say something like that out loud and I’d be ushered into an airless room to use an alligator sock-puppet to proxy my feelings. I kept my mouth shut, laid flat and shut my eyes. The doctor and a variety of assistants put me off to sleep, and despite my very worst fears, I woke up again a few hours later.

***

The nurse who greeted me in the recovery room wore dancing duck scrubs and injected something wonderful in my IV that made me revise my position on pharmaceutical interventions.

I’d never spent all night in the hospital before, and it soon became clear that I wasn’t going to sleep. It’s both eerie and comforting to watch the machines, the squiggles and beeps, the numerical representations of your inner workings. It distracts from whatever is going on down the hall. In my case, there was a man wailing and crying. The quiet shuffle of nurses on night watch. I got up and shut the door. The poor soul deserved some privacy, at least from me.

Things had gone well for me, and I wasn’t ungrateful. I passed the hours planning my life and its various contingencies. I had a novel to edit. Why hadn’t I started that? All kinds of journals are open in the summer, but I hadn’t sent anywhere, but then, I’d had other things to worry about.

Doctors had asked me about my stress levels, and I offered graduate school as an explanation. Most of them seemed dubious that a degree in creative writing was anything to get worked up over. The prevailing attitude was that I’d spent a few years being frivolous and maybe I had. There’s a certain amount of psychological adjustment required to pass from creative captivity back into the wild. I was beginning to see why not everyone can resist the urge to go native.

The nurse came in throughout the night to check my vitals, and we made small talk. This particular nurse didn’t really read books, but she watched Downton Abbey.

“Did you know the guy who played Matthew is in Cleveland?” I asked.

“No, shit. Really?”

I spent the next couple of hours researching “thing theory” and Jung’s ideas about synchronicity. I was beginning to feel foolish about the whole affair, applying rules of literature where they didn’t belong. Spend enough time crafting fiction, one can begin to believe that life has a plot. It doesn’t. There’s no objective correlative to reality. Images aren’t necessarily symbolic. One of the reason we love stories so much is that they apply pattern to chaos. As much as it may have seemed that my life had acquired its own Cetonia Aurata, it hadn’t. Does Dan Stevens have to happen for a reason? In short, no.

Coincidence is coincidence. After all, it was only two times. That’s not that weird.

But then it got weird.

(To Be Continued…)

Suzanne Hodsden is Mid-American Review‘s Technical Editor.

Suzanne Hodsden is Mid-American Review‘s Technical Editor.

Her fiction appears most recently in Crab Orchard Review. Find

her on Twitter: @zannahsue.

Intrigued. Waiting.