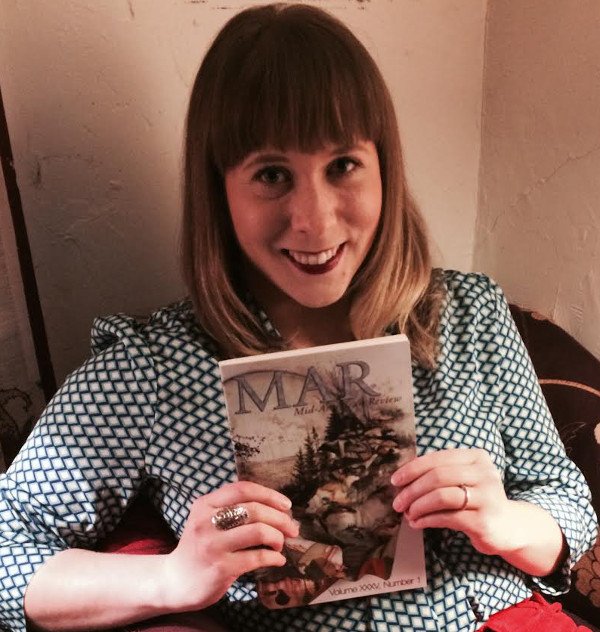

Today on the blog we have a contributor interview with Kristin George Bagdanov, whose poem “Purge Body” appears in MAR 35.1. Kristin is an MFA candidate in poetry at Colorado State University, where she is a Lilly Graduate Fellow. Her poems have recently appeared in or are forthcoming from Cincinnati Review, Juked, The Laurel Review, The Los Angeles Review, 32 Poems, and others. She is the poetry editor of Ruminate Magazine. You can find more of her work at kristingeorgebagdanov.com.

What can you share about your poem, “Purge Body,” prior to its MAR publication?

I’ve always been really good at sleeping. I took it for granted, drinking coffee right before bed and falling asleep as soon as my head hit the pillow. Then I got older. Or maybe it was grad school. And I started to notice how even at night I couldn’t escape distraction, lights and flashes and worry that kept calling me away from that deepest solitude of sleep—that time when we are lost inside ourselves with no guarantee of waking. And this poem grew out of the craving for darkness, for emptying out the exhausting brightness of daily life. While writing this poem, I also started doing a lot of research on light pollution, and there’s this really great, and I think important, book out now by Paul Bograd called The End of Night that I suggest you all read. He says that “in our artificially lit world, three-quarters of Americans’ eyes never switch to night vision and most of us no longer experience true darkness.” And I have to wonder, how is that lack of darkness harming us, inside and out?

What was your reaction upon receiving your MAR acceptance?

Happy dance. There may have been a squeal as well.

What was the best feedback you received on this piece?

Well, this wasn’t in reference to this piece, but I think it’s a useful story about feedback in general. Several years ago, after an editor had accepted a poem, I sent him a revised version to print instead. He told me he liked the previous version better and asked why I cut so much out of the original. I told him I had workshopped it and got some additional feedback, the consensus of which was to cut it down quite a bit. He replied:

“Yet another reason why workshops are dangerous to a poet’s health! In my experience, the product is rarely an improvement on the original—you can cut out the gripes from the peanut gallery, but then you lose the magical spark of the original creation.”

I was much younger then, and hadn’t learned to fully trust myself or my poems (and I suppose I’m still working on that). I’ve carried this advice with me ever since, through countless workshops and critique sessions. In the end, you have to trust your own sense of the poem, and take everything else with a grain of salt.

You’re at a family reunion and some long-lost relative asks about your writing. What do you say?

I usually start by saying “I hate this question” (in response to “what kind of poetry do you write”).

Once a relative told me he liked my chapbook, but suggested I should try rhyming more. So, there’s that.

What do you consider your biggest writing-related success?

Well I’ll define “success” as that which has helped me most with my writing, rather than some sort of prize or publication. And so to that end, I’d say it’s my time in the MFA program at Colorado State University, which I am finishing up now. I can’t believe how much I’ve grown not only as a writer, but as a reader. My experience there is what informs and will continue to inform all other writing-related successes I might be fortunate enough to have.

Your biggest writing-related regret?

Any poems printed in my undergraduate literary journal.

Tell us one strange thing about yourself that does not involve writing.

My cat is my muse.

Tell us one strange thing about yourself that does involve writing.

My cat is my muse.

Thanks, Kristin!

Laura Maylene Walter, Fiction Editor