Andrea Witzke Slot lives between London and Chicago. She writes poetry, fiction, essays, and academic work, and is particularly interested in the ways and means in which cultures, ideas, and genres intersect. She is author of the poetry collection To find a new beauty (Gold Wake Press, 2012), and her work is forthcoming or has recently appeared in such places as Spoon River Poetry Review, Southeast Review, Poetry East, Nimrod, Adirondack Review, Crab Orchard Review, Bellevue Literary Review, and The Chronicle of Higher Education, while her academic work on poetry and social change has been included in books published by SUNY Press (2013) and Palgrave Macmillan (2014). She’s been a finalist, runner-up, and honorable mention in several recent writing awards, including Southeast Review’s Gearhart Poetry Prize, Black Lawrence Press’s Hudson Award for her second book of poetry, AROHO’s Clarissa Dalloway book prize for her first novel, and the 2014 Calvino Prize for her short fiction. Her website is: http://www.andreawitzkeslot.com.

Andrea’s prose poem, “Panoply,” was a finalist in the 2014 Fineline competition and appears in issue 35.1.

Quick! Summarize your piece in 10 words or fewer.

We’re all anatomical phenomena: slowly disappearing day by day.

What can you share about this piece prior to its MAR publication?

“Panoply” is one of the twenty-odd prose poems in my recently finished novel The Cartography of Flesh: in the silence of Ella Mendelssohn. Each of the poems explores an aspect of the human anatomy, which in turn provides a kind of internal roadmap for the changes in the characters’ lives and relationships. I learned some amazing facts about the body as I did research for the poems, and was particularly fascinated to learn that we have fewer bones as adults (around 206) than we do the day we are born (between 300 and 350). Top this off with natural bone loss and the all-too-common problem of osteoporosis and we have the strange disappearing act of what it means to be human.

As to publishing these poems, though, I honestly didn’t know where they might belong. I was excited when I read MAR’s call for submissions to the Fineline competition and felt I might just be “coming home” to the type of work I love most. What a treat it was to learn one of my pieces was a finalist, and even more so to receive the latest issue in the mail, read so many amazing hybrid pieces in a collective format, and find my piece among so much work that I admire.

What was your reaction upon receiving your MAR acceptance?

Thrilled! — both to hear I was a finalist and to hear about the offer of publication even before a winner was chosen. I love the poem that won the contest, too, and was delighted to be a part of the special feature of Fineline work.

What was the worst/best feedback you received on this piece?

A friend suggested that I take the prose poems out of my novel and consider including them in a separate body of work. Although I didn’t do as she suggested, and became even more strongly invested in the belief that the novel is what it is because of them, this friend made me realize that the poems might have what it takes to stand on their own. Maybe that is the best kind of advice: advice that makes you rethink, reposition, and/or recommit. And, in this case, maybe I did all three. I’m genuinely grateful for her words.

You’re at a family reunion and some long-lost relative asks about your writing. What do you say?

“It’s my full-time profession and my passion, and everything I do and plan is structured so that I have as much time as possible for it. Luckily, I have a family that is incredibly supportive of the crazy amount of energy I devote to it.” Depending on the relative, s/he might pour me a glass of wine and say, “Tell me more,” or s/he’ll ask, “So do you use your family for inspiration?” Either way, I’d take the glass of wine, probably sigh, and say something like, “It’s complicated.”

What do you consider your biggest writing-related success?

Completing the novel The Cartography of Flesh is probably what I’d call my “biggest writing success” (a phrase I use with some sense of caution). The novel has several voices, twenty-odd prose poems, and traditional narrative chapters, as well as the larger theme of resisting and rewriting the Penelope-in-waiting myth in a modern-day setting, but it was the process of revising the manuscript over several years that makes me feel it was my biggest success. The revision was complicated by the fact that I couldn’t shake the need to revise like a poet—word by word, line by line, passage by passage, page by page. It was exhausting work and only recently have I been able to say that the novel is “finished.” Happily, I’m now at work on the next novel, with the full benefits of first-novel hindsight. The equivalent in my poetry would be the nine-page poem of anti-violence “Ring Out, Wild Bells,” (a finalist in Southeast Review’s Gearhart Prize and just released in their latest issue), which also took an exceptional amount of time and energy to write, and, truth be told, is still a work in progress despite its recent publication.

Your biggest writing-related regret?

Not trying contests sooner. I know some people dismiss contests because of contest fees, but I believe contests serve several important roles in the current writing scene: they level the playing field by requiring anonymous submissions, they offer support to financially-starved small presses and magazines (who too often aren’t supported enough in terms of subscriptions and book sales by those submitting work), and they allow writers to test the waters with different genres to see which pieces gets noticed. Plus, there are often benefits even if you don’t win; some (MAR!) sometimes offer publication to participants or offer a year’s subscription to the journal in return for the contest fee. I strongly believe that we need to support the journals we love and the equivalent-of-a-subscription-price (or x cups of coffee) contest fee seems a fair enough deal to me. I guess the key is to be choosy about where you put your money so that you’re not randomly sending work (and money!) out without focus or understanding of the marketplace in which you’re engaging. (I have a budget that I stick to, which helps.) I hope, too, that one day someone will offer scholarships to help struggling writers who genuinely have no resources or tradeoffs that will help them subscribe to more journals, buy more poetry books, and enter such contests. After I changed my mind about contests (at the end of 2013), I found myself as runner-up, finalist, and honorable mention in nine contests in 2014. But, alas, still no win! J

Your biggest non-writing-related regret?

Not putting myself out there more. Do you remember the letter that Henry leaves for Clare in Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveller’s Wife? There were some great lines that I repeat to myself sometimes as if I wrote that letter to myself, namely, the lines “move through [the world] as though it offers no resistance, as though the world is your natural element.” The fact is, I love staying home and working in a comfy, private bubble—the substance of most of my days now that I’m writing full time. But writers need to brave the world, too. That might sound surprising from someone who lives between two countries and has lived a number of different lives, loves teaching, and even loves people, but my natural instinct is to find time alone in the comfort of books and quiet familiar surroundings, and in the company of those who know me best.

Tell us one strange thing about yourself that does not involve writing.

I love cheese nachos after yoga, which sometimes means munching nachos mid-morning. Do the nachos delete the good of my yoga practice? I’d like to think not. In fact, I’d like to think yoga and nachos are naturally simpatico. I know I’m not planning on giving up either any time soon.

Tell us one strange thing about yourself that does involve writing.

Despite years of comfortably teaching in the classroom, I still get nervous before readings and sometimes want to turn the car (or my body) around and go home. Perhaps part of this stems from thinking that I should wait until I’m a “real” writer to participate in these things, a feeling I’m more likely to get when I’m actually writing, when I feel a piece is truly “finished,” or when I get a publication acceptance, which is, I’m happy to say, happening more and more frequently these days.

Do you have another favorite piece of writing in this MAR issue? If so, name it and tell us why.

“To Be Left Without A City,” the Luis Garcia Montero piece translated by Alice McAdams. The prose poems are gorgeously haunting and I was particularly transfixed by III and VII. Such beautiful lines in both Spanish and English, and a very impressive translation.

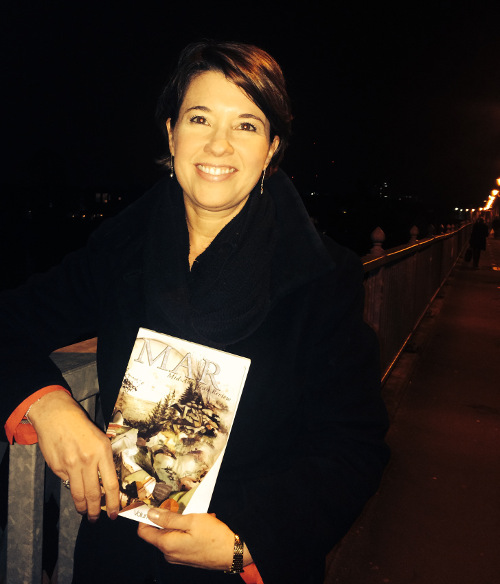

Can you show us a photo of you holding your MAR contributor’s copy?

I’ve included this in the email – a photo my husband took last month as we were crossing the Thames on Putney Bridge in London on our way to meet some friends for dinner!

Thanks, Andrea!

Laura Maylene Walter, Fiction Editor