By Sydney Koeplin

- Open up a fresh Google Doc. Change your settings from default to Times New Roman, 12pt., double-spaced. The poets tell you that the best poetry is written in Garamond, but you’re a fiction writer, so it’s TNR all the way, baby.

- Crack your knuckles, then your neck for good measure. Curl up in your favorite chair in a way you know your mom would hate: legs pretzeled, spine slightly twisted, leaning onto the finest armrest Facebook marketplace could offer. This is why your back hurts! She’s probably right.

- Ponder for an hour or two. You had had a story idea in there, hadn’t you? Something about a woman turning into a goldfish or maybe a seal. It was going to be weird and wonderful and sneakily moving. Your workshop was going to clap for you as you walked in the door, beg you to show them how you did it. Grant you your MFA right there. Ask you to run the class, even.

- Light a candle—Autumn Leaves scented, even though it’s 85 degrees in Ohio—as if to conjure the Writing Gods™.

- Write a first paragraph. Read it, realize it’s horrible, delete it. What type of opening line was this? She’d always loved using the lavender salts in the bath, but now she was a goldfish, and she found they rather stung. Stupid, stupid, stupid.

- Tap your forehead a few times like you do the busted flashlight in the junk drawer. A few good whacks should make the bulb turn on. Your bulb doesn’t turn on.

- Have a moment of understanding as to why all the classic writers were alcoholics. Think of the bottle of Costco Cabernet that is sitting in your very beige kitchen right now. Decide against it.

- Remember that you also have a bottle of whiskey a friend gifted you, aptly called Writer’s Tears.

- Decide against that, too. You’re not Hemingway.

- Try a breathing exercise. Inhale, hold, exhale, hold. Box breathing, your mom calls it. Try it again. Choke on your spit, cough.

- Find yourself on Instagram. Spend 27 minutes sucked into the feed. Impulse buy a tote bag with a frog in cowboy boots on it. Open your family group chat and watch the video your dad sent of a duckling who is friends with a goat.

- Look up from your phone and wonder what you’d been trying to accomplish in the first place. It was MFA-related, right? It was, oh—

- Unpretzel yourself and throw your phone—okay, gently place it—in your desk drawer.

- Channel Anne Lamott and her Shitty First Drafts. Write. Finally, just write. It’s awful. There are typos. Plotholes you can drive a combine through. Write like the muses speak through you in disjointed, misshapen prose. Just let it happen.

- Shut your laptop in a daze after a few hours curled over it like a cooked shrimp. Rub your eyes, unfurl your legs, shake your head, and feel a few marbles roll around up there.

- Spend several days agonizing over the utter filth you’ve just written. Swim laps at the rec center, and hope you don’t run into any of your students while you’re in a swimsuit. Eat a sub sandwich. Call your mom and tell her you’re a failure, ignore all her very sound advice to take a chill pill. During this time, you’ll seriously consider quitting the MFA and joining the vampire cult in Dayton.

- When it’s marinated long enough, cautiously reopen your Google Doc. Read through your draft with your hands over your eyes as if they’ll shield you from how much you suck. Get through a few paragraphs, and sit up straighter. Read a few more and put your hands down.

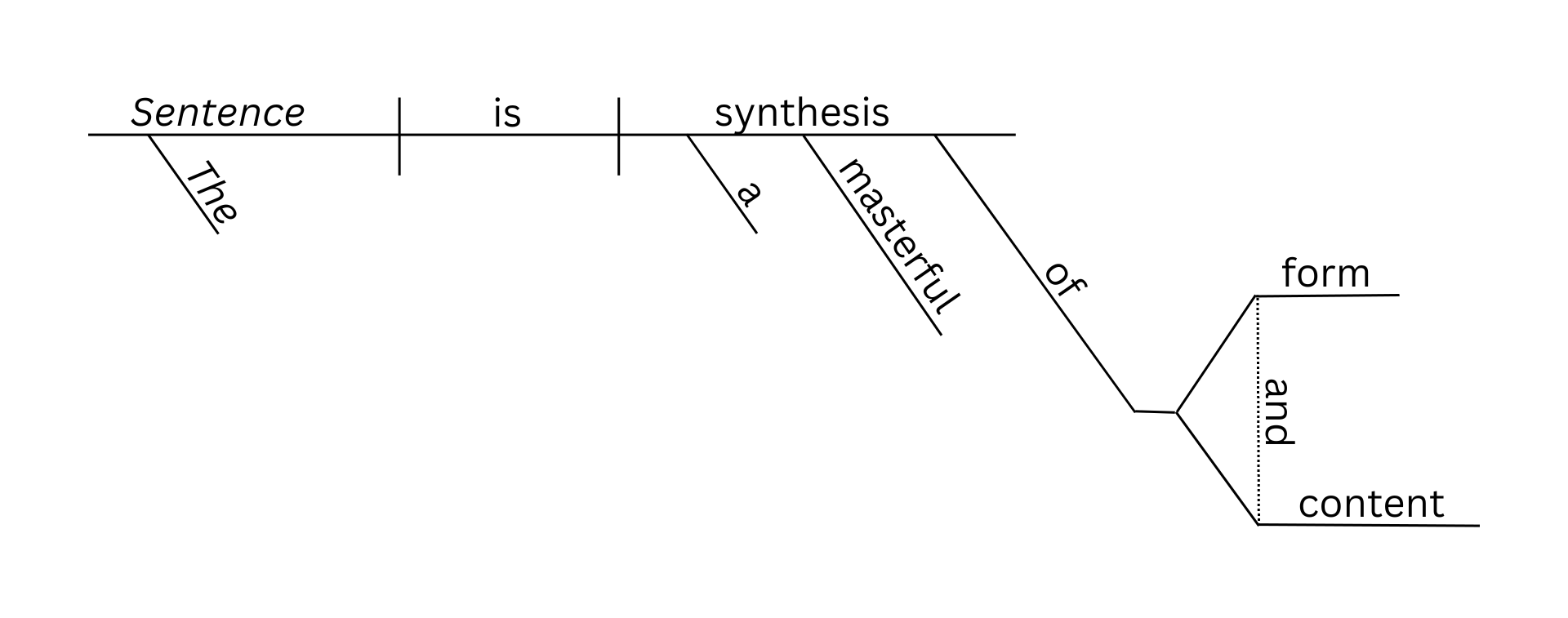

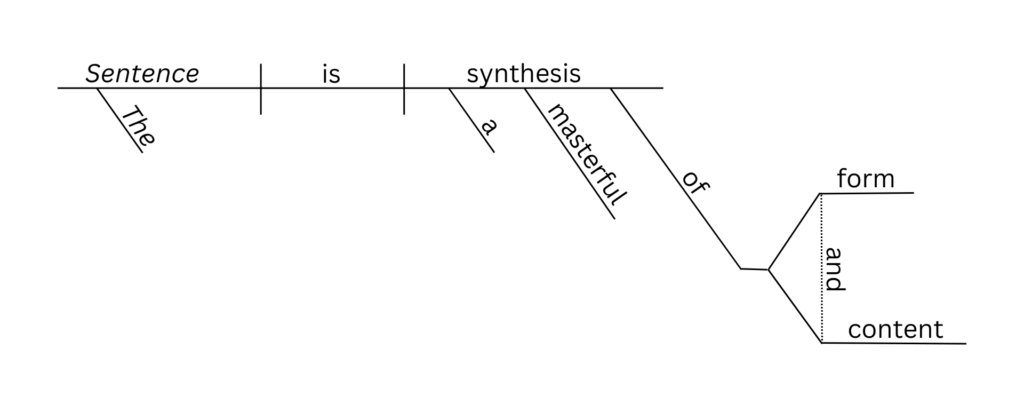

- Realize that what you’ve written isn’t as shit as you thought. It’s salvageable, in fact. At times, you’re even clever! At times, your sentences are well crafted! Who would’ve thought? Not you.

- Spend all the time you have before your workshop submission deadline revising, revising, revising. Something’s deeply wrong with the intro, but you don’t know what exactly. And what happens, ultimately, when the goldfish woman is flushed down the drain? That’s anybody’s guess.

- When it’s as good as it’s going to get, when you’re trembling and spent, email blast your cohort with your attached story exactly one minute before the deadline, question marks and all.

- Imagine your workshopmates snickering over your story the entire weekend, wondering how it’s possible you could’ve ever been let into the program in the first place. No wonder she got in off the waitlist, you hear them laughing somewhere in the corners of your brain. You may revisit that notion to join the Dayton vampire cult.

- Slink into workshop on Monday like a dog who just found a half-eaten Krispy Kreme in the dumpster and is about to barf it up. Wait for the shuning that—miraculously—never comes.

- For an hour and a half, scribble down all your classmates’ comments in handwriting that is hardly legible. Learn that what’s wrong with your beginning is that it actually starts on page three. Bounce ideas off of them where the goldfish woman goes when she is sucked down the drain. Stain the side of your hand inky blue.

- Realize that you have survived the workshop, and get a brownie from the dining hall to celebrate. This step is very important. Unless, of course, you have an ice cream bar waiting in your freezer, in which case you can save the meal swipe and have your treat at home.

- Repeat this process until you finish your MFA, get hit by a bus, or are microwaved by the inevitable heat-death of the universe. Whichever comes first.