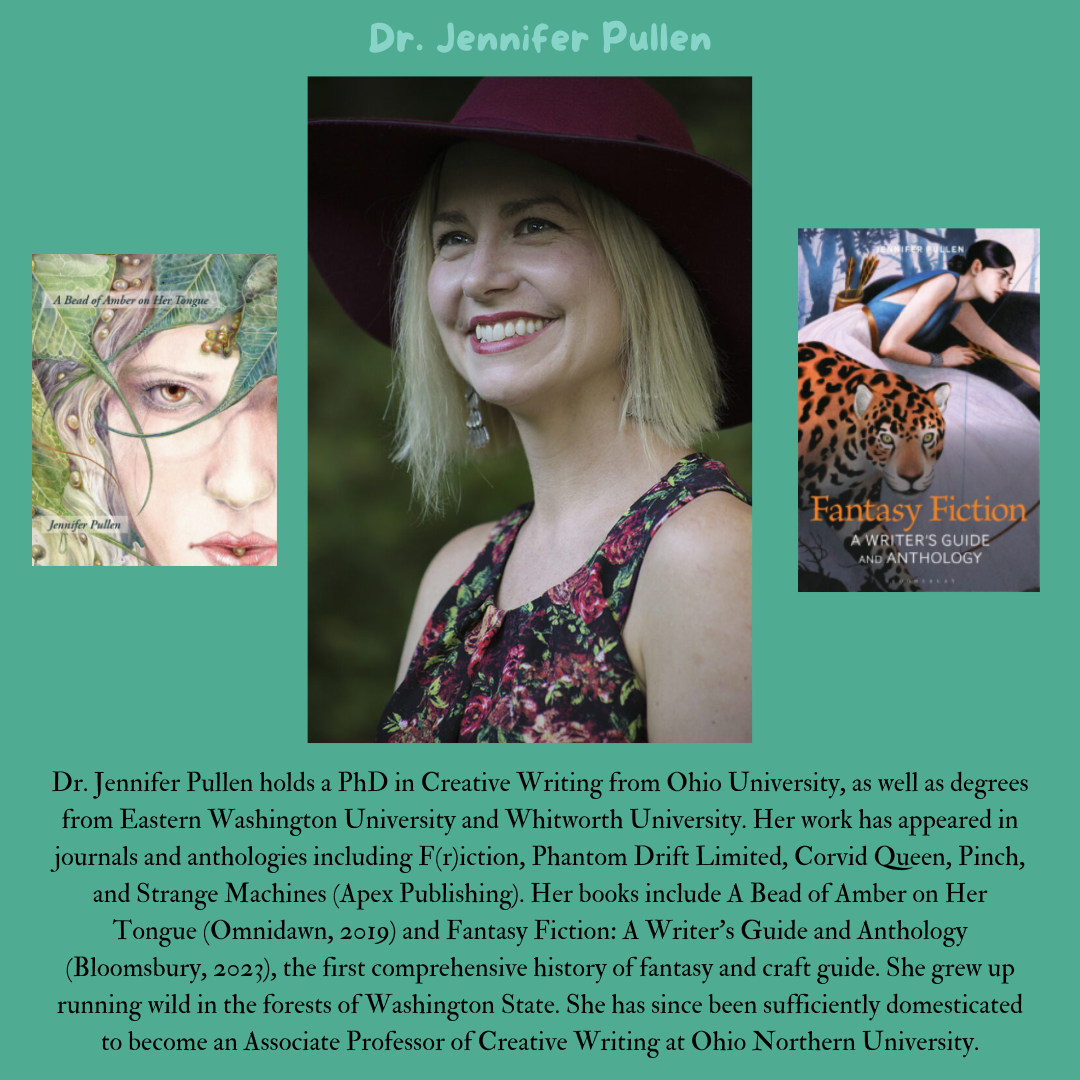

Photo Caption: Dr. Jennifer Pullen

Jennifer Pullen holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Ohio University, as well as degrees from Eastern Washington University and Whitworth University. Her work has appeared in journals and anthologies including F(r)iction, Phantom Drift Limited, Corvid Queen, Pinch, and Strange Machines (Apex Publishing). Her books include A Bead of Amber on Her Tongue (Omnidawn, 2019) and Fantasy Fiction: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury, 2023), the first comprehensive history of fantasy and craft guide. She grew up running wild in the forests of Washington State. She has since been sufficiently domesticated to become an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Ohio Northern University.

At Winter Wheat 2024, Dr. Jennifer Pullen was the keynote speaker. Between the festival chaos, Dr. Jennifer Pullen sat down with us for an interview which appears below. This interview was conducted by MAR Assistant Editor Jaden Gootjes.

Interviewer: How did you start writing?

Jennifer Pullen: Honestly, I’ve been writing my whole life in a really nerdy way. When I was a child, I loved stories so much, and my parents read books to me constantly. Our house was full of books. So when I was five, I went up to my parents and said: “Mom and Dad, I have an idea for a novel.” They said: “Well, you can’t write yet. And I responded: “That’s why I’m going to dictate it to you. I’m going to tell it to you, and you will write it down.” My parents were very tolerant of me narrating some wild story that had a wizard, a princess, and a magical cat that was cursed. That’s all I really remember about it. So, I guess the storytelling impulse is something I’ve always had. As soon as I was able to scribble for myself, and I didn’t have to impose upon my parents, I did.

As far as deciding I wanted to become a writer, that was probably when I was around 13 or so. I went to a festival in Spokane, Washington called Get Lit, and they had a section that was aimed at teenagers called The Writing Rally. I went, and I had this moment where I realized: “Whoa, there are people who make teaching and writing their life.” I thought: “I want to do that.” So, I was determined to make writing my life from a really, really young age. Little did I know everything involved in that, but I knew that that was what I wanted.

Interviewer: In 2023, you published Fantasy Fiction: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology, which has been called the first comprehensive history of fantasy craft guide. What were some of the challenges and successes you encountered while writing this book?

Jennifer Pullen: I would say some of the biggest challenges came from the fact that I signed the contract to write the book with Bloomsbury, and then shortly thereafter COVID-19 happened. So, when trying to get permissions for the anthology, it became very complicated to get ahold of editors, publishers, and agents when everybody would have gone home. So, choosing the stories and doing the permissions while on lockdown was really surreal and strange. It added communicative challenges I hadn’t anticipated.

The other challenges I encountered had to do with the fact that I had more to say than words I was allowed to write. I am a chronic overwriter, and after I wrote it, I looked, and I thought: “Oh no, this is like 30,000 words over my contracted word limit.” So I had to go through and really, really pare it down and think: “Okay, I know I have endless amounts of things I would like to say, but what is essential for what I’m trying to accomplish rather than me just being a giant nerd?” So that process was really interesting. Also, it was just interesting to be trying to write the textbook and work on a novel at the same time. I would be essentially working on the novel–sending portions of it and drafts of it out to my agent at that time–then while he was looking at it, which would take around six months, I would write chapters of the textbook. So, I was sort of alternating. I was still teaching a 4-4 load–four classes each semester–and alternating between critic-scholar brain and artist brain. That was a fascinating sort of challenge. It kept me grounded when writing the craft portions, because I was writing about the craft of fantasy as I was trying to write a fantasy novel myself.

Interviewer: What were some successes you faced while writing Fantasy Fiction: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology?

Jennifer Pullen: I felt confident in writing the book, and I knew that this was something I knew a lot about. It had been the focus of my research and, frankly, just my lifelong, nerdy passion. But what startled me was I didn’t fully understand how much I knew until I sat down to write, and I was able to pull it out of my head. Then I thought: “Oh, I can actually just remember all of this.” And that was a really validating thing.

I think as women, we are often not taught to think about our own expertise or to feel like you could be say: “yes, I know a lot.” So to have the validation of realizing that I was able to write so much of it basically from memory made me feel really good and confident in myself as a scholar and teacher. I also really enjoyed getting to write the book that I wished existed my whole life, because I spent my entire time as an undergrad and graduate student in a world in which fantasy and science fiction–really any so-called genre fiction–was hardly taught in the classroom. I took a Tolkien class in undergrad, but the professor chose to teach in the course in the theology department and they were interested in the books’ theology, not in their craft. So, getting to do what I’d been doing informally, being an evangelist for the genre, and getting to actually put it out there and make the book that I wished existed was a really fabulous experience that made me really happy.

Interviewer: I watched an interview of yours where you talked about the influence of The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle on your work, which is my favorite movie. Could you talk about the book or another book or author that has had a significant influence on your writing and appreciation of fantasy?

Jennifer Pullen: Well, The Last Unicorn–the movie and the novel—was definitely the big one, formative in my youth. If you want an explanation of my entire aesthetic, that’s it right there. Sort of sad, melancholy, and lightly gothy, but also beautiful at the same time and hopeful. I’m really interested in the tension between sadness and beauty. Beyond that, a novelist that I’ve really, really admired for many, many years is Guy Gavriel Kay. He’s a Canadian fantasist, and he’s considered our best living historical fantasy novelist. He essentially writes mostly single one-off novels. He’s mapped the globe and created fantasy versions of different medieval cultures. He researches really heavily for each period and place. Then, by changing aspects of period and place, he’s used his fantasy to turn up the volume of particular aspects of place and time. And his work is really beautiful and very prose-forward. He does a lot of really interesting experimental stuff in some of his more recent works. He’s retold a portion of what happened with the Crusades, but entirely from the perspective of civilians or people who get caught in the edges of war, characters who would never normally be the center of a fantasy novel because they’re not involved in the big scheme of the conflict. They’re just people. His novel, The Last Light of the Sun, is one of my favorite books. The end makes me cry every time because all the pieces of the characters and the world and the conflict that’s been building comes together perfectly and snaps into place. He does some really interesting, masterful things with point of view as well where I think: “are you allowed to do that?” He pulls it off, but you’ll encounter a side character for a moment, and they’ll live through something they probably shouldn’t have. Then, he’ll move 30 years down the road, and you’ll get a brief explosion into the future over around a page of the character’s life and how this moment where they should have died impacts them. It’s incredible. If I could ever pull off some of the stuff he pulls off, I would be a happy woman.

Interviewer: That really shows you the kind of work that fantasy and fiction can do outside of themselves. You talked about how when you were a young writer, there wasn’t a lot of emphasis on fantasy and science fiction in academia. But how would you describe the state of discourse in fantasy writing communities and academia today?

Jennifer Pullen: I would say it’s better. I think now if people outright prohibit writing fantasy, you’re not in vogue. When I was 16 and taking classes at a community college, I turned in a retelling of “Thomas the Rhymer.” It was handed back to me, and I was told to “write a real story without fairies.” That was very common and normal at the time. I think most of academia is aware now that’s fuddy duddy, and you probably shouldn’t do that. I think that’s been a pretty radical change, particularly as the boundaries between “realism” and “genre” have gotten a lot of fuzzier. I think we’re in a transition period where people realize that anti genre bias is a social construct. But, I don’t think most programs in academia have completed the shift to actually offering classes in genre. It’s entirely possible to have a PhD in American literature but have ignored fantasy entirely, versus I would never have been allowed to just pretend realism didn’t exist. I think we’re in that period where the hostility has decreased but coursework–especially at the graduate level for people qualifying–has not shifted to include teaching people about fantasy or thinking of it as essential. You always see on the Creative Writing Pedagogy Facebook page people saying: “all right I have an undergrad who is applying to MFA programs, who’s genre friendly?” and you still have to pour over the faculty and classes. There are a few programs that specify popular fiction as their emphasis, but that alone is actually evidence of the fact that it’s not fully included. Nobody would ever say “this is an MFA for people who want to write realism.” You would never feel the need to create a realism-emphasis MFA program. So, hostility is way down. But I don’t think we’re at the point where people recognize you should and must include an inclusive genre program.

Interviewer: You grew up in Washington. How does the natural world, or the world outside of fiction generally, influence your creative work?

Jennifer Pullen: Oh goodness, so much. I grew up in Washington state, like you said, but also in a little valley surrounded by mountains on all sides. I was homeschooled, and my parents are bookish scientists. My father is a forester, and we grew up on 70 acres backed by thousands of acres of state land. So, I was kind of a feral woods and library child. I was always going outside with my mother and identifying plants, and if my dad has a religion, it’s nature. So, treating the natural world as vitally important and sacred in and of itself was very much a part of my childhood and my growing up. For me, I think stories and nature are the two cores of my life, and that’s why living in the flat cornfield part of Ohio causes me a lot of problems. I see all the corn, and I think: “industrial monoculture!” and get really angry every day when I drive through it.

I feel like so many of the storytelling traditions I’m interested in–a lot of fantasy as well as folk tales and myth–come out of the understanding that there are forces that are larger than humans. Humans are not the center of the universe, and I think that is something that is different in a lot of fantasy, fairytale retellings, and myth as opposed to realism where individual human experience is centered. Human experience is important, but that’s not all it is. There are always larger things and forces that influence individual decisions. Be it larger, like social forces, but also the natural world. I think magic in a lot of fantasy is, in many respects, an acknowledgement of the fact that humans can’t control everything and there are things beyond us. So, for me fantasy and nature writing go like this [Pullen laces her fingers together]. I have a hard time separating them.

Interviewer: Your [short story collection], A Bead of Amber on her Tongue, was published in 2019. What was the process of world building and character creation like while writing?

Jennifer Pullen: That is a little chapbook of two short stories from my dissertation. They are feminist retellings of myth. I had a big project that I was working on all through my PhD program where I was retelling myths and fairy tales from the perspective of characters who I thought had been silenced in the original versions of the stories. I was trying to embody them and focus on their experience. The characters were mostly women and retellings of Greek myths and fairytales. In [A Bead of Amber on her Tongue] I have the retelling of Aphrodite in Hephaestus and the golden net. In Greek mythology, Hephaestus, who’s the god of smiths, makes a golden throne and gives it as a gift to Hera and Zeus, but it’s a trap. Hera can’t get off it, and Zeus says: “Free my wife.” Hephaestus responds: “Only if you give me your daughter Aphrodite as my wife.” So, Aphrodite just gets traded away to the God of Smiths even though she’s a goddess. She’s still property, which is just trash. She’s the goddess of love, and she’s now married to Hephaestus. But she has children with several other deities. There’s a story where she has a long running affair with Ares, and Hephaestus catches Aphrodite and Ares in bed together and throws a golden net over them and traps them. Then he calls all the other gods to see Aphrodite in her shame. That story always bothered me. So, I rewrote the story from Aphrodite’s perspective.

The other story is a retelling of the story of Helen as she runs off with Paris. She’s so often vilified and treated as the cause of the war, and I really wanted to think about that from her point of view, what that would have been like. I wanted to be accurate to the myths; I didn’t want to change the plot. That gets done plenty. But what I wanted was to tell these stories and really, really take seriously what it would be like to be Aphrodite and Helen, who are both very powerful and very powerless, and infuse the stories with a deeply human sense while also maintaining the feeling of myth. So, I already had the plot; I just had to think about the individualized experiences and try to get the sense of the ancient world to come off the page without it being a history lesson.

Interviewer: We’ve vilified female characters in stories for centuries, and today in TV shows and movies people still fall for it.

Jennifer Pullen: They sure do.

Interviewer: So, what do you hope readers will take away from your work?

Jennifer Pullen: Kind of depends upon what it is that I’ve written. But in terms of all the short stories that were part of that project, I really just wanted people to think about what the stories are and what culture tells itself. Because that’s one of the things that’s fascinating about myths and fairytales, that they’re retold repeatedly again and again, and we don’t even have the capacity to discover what the original is because they’re oral. We can’t even verify where it began so every version that exists is technically a retelling, and it reflects what the reteller’s cultural values are and what they believe. Every retelling is a kind of a commentary on the ones that the writer had seen or heard before. So, I really want people to think about what stories we are telling to ourselves and what do they say about our culture? What is the relationship of the past to the present? I think the fact that these stories are so consistently retold shows that humans don’t change that much; we just put different dressings on our behaviors. If we can accept that we are part of the past–even as we’re living in our present–we can have more ability to actually change things. We don’t act as though we exist in a vacuum.

Interviewer: I think one of the big draws of myth is its ability to stand test of time and still be relevant year after year after year because it’s just plainly about human nature.

So, I want to end with what advice you would give young writers today.

Jennifer Pullen: Oh goodness. Read a lot. Read, read, read so much and read widely and deeply and then just keep writing what you love and trying to make the best version of whatever it is that you love. Take good advice; take advice from other writers; learn from your classes but use advice and what you learn to become the best version of whatever kind of writer you want to be. I had mostly teachers who wrote realism, but I still learned a lot from them. I didn’t let them make me a realist writer. I just learned things from them anyway and read piles of books. I know sometimes people want to be writers, but they don’t read a lot and that’s just not going to work. You’ll never to be any good, frankly. So remember what you love and keep working at it.