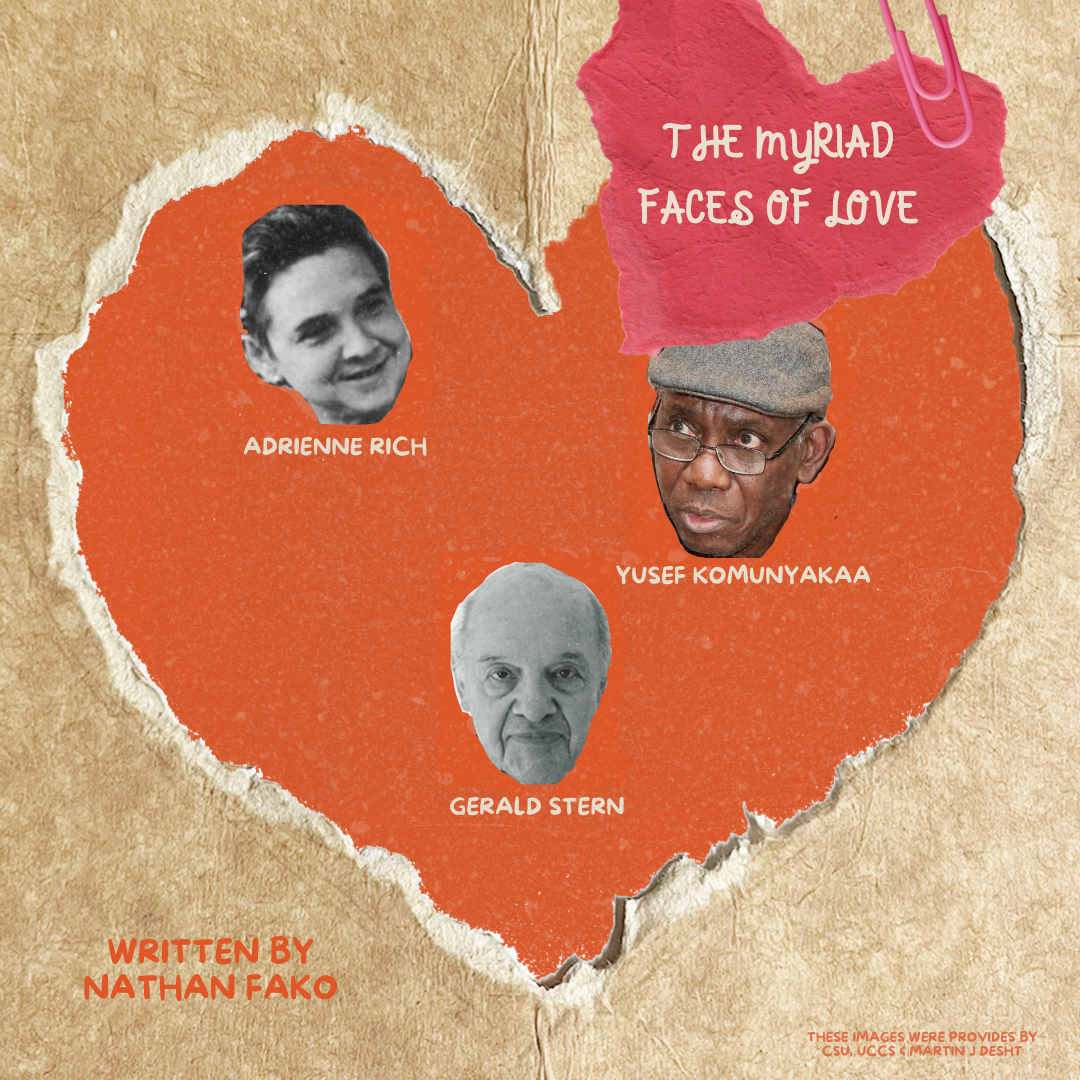

What poetry by Adrienne Rich, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Gerald Stern can teach us about our own hearts and the ways we love.

By Nathan Fako

When we think about poetry, our minds probably go to high school Language Arts classes. We get a flash of a Shakespearean sonnet, we feel again the deafening silence as the class struggles to “get” the poem. Or perhaps we think of Neruda, Rumi, or Billy Collins. Mary Oliver. The truth is, I think, that most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about poetry. Poetry doesn’t pay the water bill or change a diaper. But there are moments in life when poetry becomes the only appropriate food for the heart and soul–falling in love, for example. How do you express the way someone makes your heart explode? Say you’re a teenager again. Maybe you make them a mixtape, or a Spotify playlist. Maybe you even venture to write them a love poem.

Some of the first poetry I wrote to show to others was in the form of love poems for my first girlfriend. I still remember vividly the feeling of pouring myself into those poems–just as vividly as I remember her telling me the poem I gave her didn’t really say what it was trying to, and that I should “try again.” Well, at least she gave me another chance.

So what separates strong love poetry from weak love poetry? We know love is one of the great themes. These are well-tread waters. Think of the bright-eyed Romantics or the ravings of Allen Ginsberg. Everyone, hopefully, has been or will be in love at some point in their lives. And what about platonic love? Love poems of brotherhood, sisterhood, love for the community, the city… the list of types of love could be endless. Gwendolyn Brooks said real art is that which endures, or something to that effect. A poet, I think, is one particularly suited to discuss love. To question it and its many faces. So here are three poems, by three different poets, and a bit of explication on the ways in which they have loved.

Adrienne Rich’s Twenty One Love Poems

“What kind of beast would turn its life into words?” So begins the seventh of Adrienne Rich’s Twenty One Love Poems. This is a series of poems I believe everyone should read for themselves, as they are visceral, full of longing, and intensely crafted. Broadly, Rich uses these poems to invent and examine a type of love that could exist “openly together”–she was gay, fighting for liberation–in a city, among others, where the lovers could be “like trees.” Inevitable. Natural. Throughout the poems Rich’s speaker examines a kind of love “where grief and laughter sleep together.” But let’s go back to the seventh poem.

Poem “VII” utilizes a form I have come to know as the interrogation form. Every statement in the poem takes the pose of a question. When we think of love poetry we think of pouring out the pitcher of the heart. Not here! Rich’s speaker turns against their own heart and its actions as though they were enemies. She questions herself, her right to language, and her battle for gay liberation. She writes, of her lover:

or, when away from you I try to create you in words,

am I simply using you, like a river or a war?

Through this speaker’s interrogation of the self, of the writing self to be more specific, we see the marionette love and language make of us. So while this is a poem about love, in a collection of poems about love, Rich has done something original and enduring. She turns to the self and interrogates it. How dare I turn the subject of my love into an object of my language, she seems to ask. In so doing, Rich brings us into close proximity with the speaker’s psyche. This is the true magic of the poem, and why her collection succeeds where others might fail. Rich’s poems pull us forcefully into a space that is lived in and inhabited entirely by the experience of being in love, with all of its messy questions and ruminations. Here are love poems that don’t proclaim to be the most in love of all, or the most moving. But they command their singularity. So let your love poems take a new shape. Turn a question towards your own heart and follow the poem into a “country that has no language,” a poem totally your own, “heroic in its ordinariness.”

Another approach to love we may be more familiar with is the consideration of the body. Oh how many young hours spent thinking of nothing but the touch of another’s hand in your hand! But what about self-love? In this poem, Komunyakaa, like Rich, turns the lens towards the self. This is a poem which is widely available on the internet–go listen to him read it.

Komunyakaa has spoken about “a poetics of the body” and this is tangible here in “Anodyne.” The lens of the poem moves slowly over the speaker’s body, proclaiming love along its path. He says:

I love my crooked feet

shaped by vanity & work

shoes made to outlast

belief. The hardness

This poem is in free-verse, and the short lines propel us down along the language. Komunyakaa’s speaker takes his time in consideration of the body, the “quick motor of each breath,” the “big hands,” and the place it has come from, “the deep smell / of fish & water hyacinth.”

So as we enter the season of love, Komunyakaa’s piece invites us to extend some of that heart power towards our own bodies. What might that look like, a love letter to yourself?

Gerald Stern’s “Let Me Please Look Into My Window”

Finally, we get to Gerald Stern’s short poem. This is another poem that you can find easily online through a quick search, and it is only ten lines long. While I won’t quote the poem here, I’ll summarize so that I can highlight two devices that it employs for effect. In this poem the speaker longs to return to a time when they lived in New York. They want to look into their window, to take a walk down Broadway and pass sights with which they are familiar.

The first device Stern uses is anaphora, the repetition of a phrase. In this poem it occurs at the beginning of a sentence. You may think of the chorus of a song, or a spiritual. The anaphora in Stern’s poem is the phrase “Let me.” This phrase also contains the second device, which I would call a speech act, and that speech act is the appeal. The speaker is repeatedly appealing to someone, in this case the god of memory in their own head or some higher power, saying please let me go back. Let me have that time once more. At the root of an appeal is a desire. In this poem, the desire is fueled by nostalgia for a time past. But the subject of love, interestingly, is not just the past but the city as well.

What might a love poem to a place look like? A neighborhood park you once idled away hours in with your friends after school, a certain booth in the family restaurant where you babysat while your parents worked… go write the love poem!