The Sentence by Matthew Baker. Ann Arbor, MI: Dzanc Books, 2023. 140 pages or 1 page, depending on your definition of a page. $31.95. (Accordion edition.)

—. Berlin, GER: Round Not Square, 2023. 1 page. €170. (Scroll edition.)

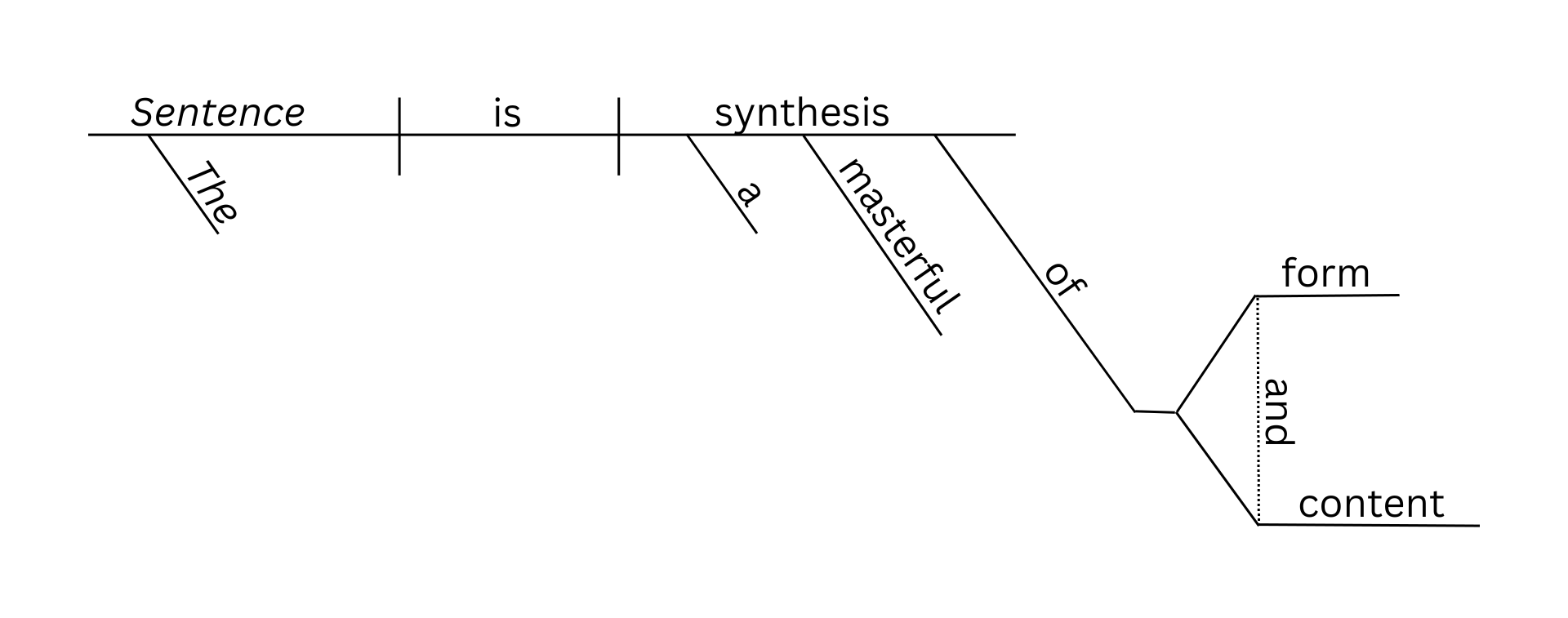

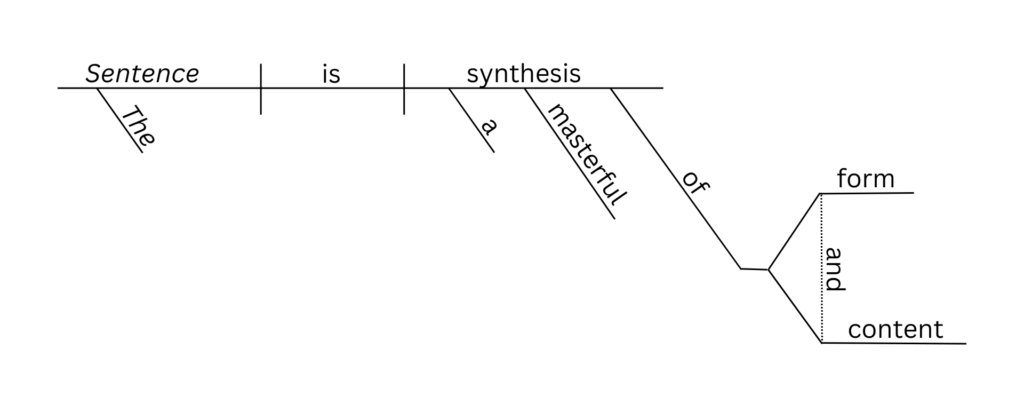

Matthew Baker’s The Sentence is a gripping graphic novel – if you put the emphasis on graph, as in a sentence diagram … and if your definition of “novel” is based on page rather than word count, because this engrossing work is a single diagrammed 6,732-word sentence. The setup may sound gimmicky, but the “gimmick” and the story itself are completely inseparable, coming together to make a work of art much greater than the sum of its parts (and the diagram form is much easier to read than it appears!)

The narrator, grammar professor Riley, has a fraction of a second to grab one item from their office as they are suddenly rushed into the unknown, away from the new dictatorial government’s unfounded treason charge against them. That one item they instinctively lunge for: a book, “the seminal text in the art of the sentence diagram … (a system for imposing order over chaos, for mapping the rough terrain of the language (the secret trailways that logically linked the words together,) for depicting the hidden architecture of a statement (the structural supports that prevented a collapse in meaning) …” This system serves as an anchor for Riley as they try to adjust to life on an off-grid anarchist compound as a very organized autistic person. Putting the story in diagram form embeds the reader under Riley’s skin by presenting reality in the orderly way they process it. The contrast between Riley and the community they come to care for is a very compelling conflict. Trying to decide between the lawless vision of their friends and the oppressive but lawful government they resist, Riley laments, “I would be forced to choose between friendship and chaos and loneliness and comfort and might die either way …”

Even the book-as-object mimics Riley’s thought process and brings the story to life in your hands. The hardcover, 70-foot-long accordion-folded sheet of paper that accommodates the diagram structure resembles Riley’s brain: neat, focused, and fragile. While toying with the book (naturally I unspooled sections across my apartment floor a few times) it occurred to me that the book is like a single thread that you pull at or comb through as you read, that continuously unravels or untangles Riley’s brain.

I just cannot get over the craft features of this form. It’s surprisingly well-equipped for pacing. As you trace through a long tangential clause, the line on the left-hand side tying it to the relevant upcoming story beat continues steadily downwards, often building suspense and always providing the assurance of order that sets Baker’s narrative apart from other stream-of-consciousness styles. At the end of a long tangent, I would follow the trail back to the point that triggered it, assess the action again in light of the new information, then flip forward once again with the background neatly compartmentalized. This back and forth motion held the story together like a backstitch, securing every lengthy description in place. It reminds me somewhat of the chronological back and forth I enjoy in Toni Morrison and Gabriel García Márquez’s writing, but the motion is spatial rather than temporal.

The Sentence asks us, what happens to an orderly system (of language or law) when it is stretched to contain an entire life? An entire people? Not only that, but the book offers itself as an exhibit of its own study in such a clever way. As a poet and poetry reader (not to mention a book arts geek), the novel struck me as a textbook example of how form and content can work together, and I’ll now be using it in the creative writing class I teach this fall.