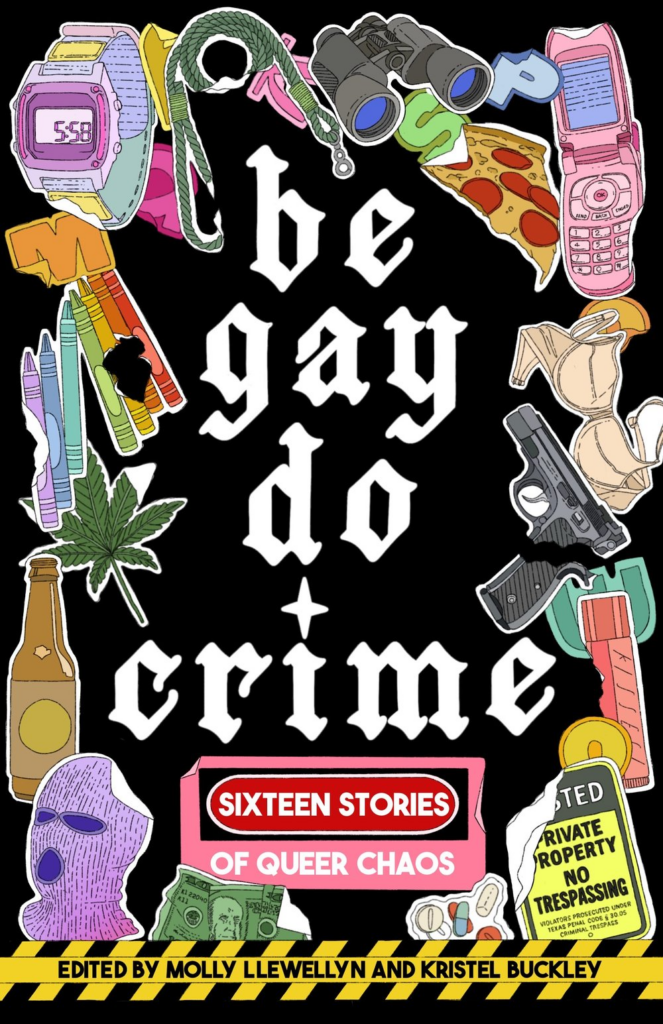

Be Gay Do Crime edited by Molly Llewellyn and Kristel Buckley. Ann Arbor, MI: Dzanc Books, 2025. 278 pages, $17.95. Paper.

Photo Description: Front cover of collection.

Photo Credit: Dzanc Books (buy the book here!)

Book review written by Hannah Goss

With the increasing anxiety about LGBTQIA+ rights in America, this collection seems timely in its exploration of queerness, transgression, and love during economic, environmental, and other disasters. Edited by Molly Llewellyn and Kristel Buckley, these sixteen short stories, Be Gay Do Crime, live up to the cover’s claim to depict queer chaos. These characters exhibit chaos through not only crimes like trespassing, kidnapping, and drug dealing, but also lesser transgressions like cursing exes, entering a children’s coloring contest, and watching the neighbor’s TV from the yard. This collection showcases a range of queer experiences from a transwoman’s experimentation with a stolen drug, “Dysphorable,” to Ghanan-British women debating having children in a post-Brexit Britain, to a second-person narrator thinking about a bad hair removal as a “reaction to manhood.” Each of these stories is revealing of the desire to be human amid a world that represses identity.

Within these stories, these characters struggle against systems of power and use these transgressions as a means of exercising agency. In “It’s a Cruel World for Empaths Like Us”, Soula Emmanuel depicts a narrator caught feeling powerless and invisible in corporate life, turning to threats via phone calls when their hair lasering goes awry. In a similar resistance to power, Priya Guns’ “Make Life Great Again,” follows a custodian’s observations from inside the White House bathroom with a familiar president watching water shortages impact the nation while he pursues a volcanic island expedition, ignoring the indigenous population that inhabited it first. Meanwhile, the narrator catches two women conspiring to assassinate the president in the bathroom stalls. Other stories more explicitly connect desire to economic inequality through Temim Fruchter’s “Redistribution” in which the main character M steals as a means of reclaiming some power she lacks, thinking each stolen object is earned from the loss of an ex. “The Meaning of Life” by Myriam Lacroix explores two women finding themselves destined for motherhood in the alley behind their apartment building where they find an abandoned child. They fear taking the child for medical care, losing custody, and finally ending up in a standoff with their son’s biological mother when she kidnaps them. These stories paint crime as a necessity, a desperate act born out of inequality from wealth, corporations, and other indifferent institutions, yet still, these characters must confront the consequences whether relational or legal.

The characters that span this collection are messy, unapologetic, and somewhat unlikable but also deeply human in their conflicts. The narrator, Iris, of Anna Dorn’s “Bad Dog” is self-sabotaging and deflecting of blame. Yet as she dresses up like her twin to try to break her engagement up, she’s forced to confront that, like the dogs her sister’s fiancée rehabilitates, there are no bad dogs. Perhaps, she has some responsibility to take for her life choices rather than blaming her life’s troubles on the dog who scarred her as a child. Alissa Nutting’s “Peep Show” narrator performs sex with her girlfriend because she thinks her boss’s dog that she stole is a robot he’s watching them through. It gives her the confidence to perform well at work and receive a promotion but at the cost of her relationship. This story explores the nuances of having to be straight-passing at work, the thin line of being sexually available but not sexually promiscuous to a male boss, and the inequality of being a white woman breaking the law versus a woman of color. The struggles of these characters are tangible, and their desires for family, love, and belonging are affecting. Each of these stories feels current and insightful in their exploration of queerness and in positioning crime as a means of protest, of reclamation, and of necessity.